An Archive as the Result of ‘Engaging with Art Every Day’ - The Art & Project Archive

Ton Geerts

In 1979, the artist Ulises Carrión (1941–1989) decided to turn his Amsterdam-based artist’s book shop and gallery, Other Books and So, into an archive. Carrión’s Other Books and So was a pioneer in artists’ publications, ephemera and mail art. In its day, the gallery-cum-shop was an important meeting place for many international artists. A year later, he reflected on the remarkable transformation of Other Books and So in Artzien art magazine:

I suspect that people associate the word ‘archive’ with inaccessibility. Archives are for specialists, difficult for the general public to access. And this is in sharp contrast to bookshops or galleries, places that are open to everyone, where people can meet other people, talk out loud, exchange information and so on.

However, as Carrión later writes, there is one essential difference: ‘In a bookshop/gallery, all visitors are potential customers, whereas in archives, the economic factor does not come into play. That is why archives can afford to deal with things that are not for sale.’

When Carrión was asked why he went from shop to archive, he replied that the archive

didn’t result from any deliberate plan, but directly from my life. . . . In my case, the archive is the result of engaging with art every day in such a profound way that, at a certain point, the archive became an artistic creation. . . . I consider it a work of art.

According to Carrión, his archive includes ‘books that I love (artists’ books, visual poetry), mail art, documentation, private correspondence, publications about visual arts expressions that I engage in myself – sound, postcards, scrapbooks, performance, video’. It is accessible to everyone, because: ‘An archive without visitors is not an archive.’1

Carrión and Geert van Beijeren and Adriaan van Ravesteijn were undoubtedly aware of each other’s activities, although there is no actual evidence of contact between Carrión and Art & Project. Especially in the early years of the gallery, Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn saw it as a space that made art available, as well as information and documentation, artists’ books, catalogues and other publications.2 The role that documentation plays in the realm of conceptual art, where works of art or even entire exhibitions can consist of nothing but documentation, may have something to do with this.

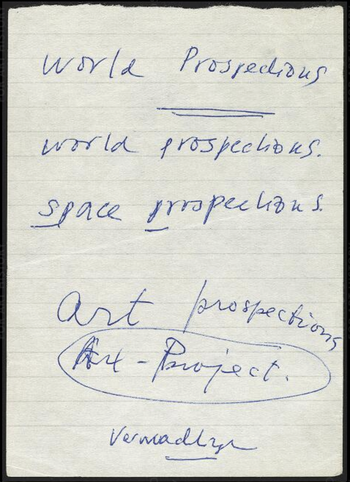

First 'draft' about the name Art & Project, RKD Archive Art & Project, 202

Mainly because of its limited space, the gallery does not function primarily as a meeting place or ‘shop’ in those early years, unlike Other Books & So. Its main means of communication are the Art & Project Bulletin and the many mailshots sent to keep interested parties informed of activities. Van Ravesteijn and Van Beijeren, the latter a librarian at the Stedelijk Museum for many years and later a curator at Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, collect a wealth of artists’ books, catalogues, invitations and posters, especially on the subject of conceptual art. Even after the heyday of conceptual art in the mid-1970s, the duo continued to intensively collect documentation on their own artists and their work, as well as on other artists they admired. Their collecting frenzy is not limited to the aforementioned documentation, however; everything that goes on in the gallery is also documented and classified, down to the smallest detail, from receipts for ordering stationery and buying furniture to train tickets. Year after year, unnoticed by the outside world, and perhaps even by the two gallery owners themselves, an extraordinarily extensive and meticulous archive develops as a result of both of them ‘engaging with art every day’, as Carrión put it.

The Art & Project archive is currently part of the RKD - Netherlands Institute for Art History in The Hague. The transfer was the result of a deliberate choice and a lengthy process.3 Van Ravesteijn spent years preparing and supervising it and after Van Beijeren’s death in 2005, the process gained momentum. The correspondence with the RKD on the subject can fill archives by itself. Van Ravesteijn sometimes closely resembles the protagonist of Ilya Kabakov’s The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (1996) – a man who, in his room, filled with papers collected during his life, tries to name and connect everything.4

Jar of red ink used to sign Bulletin 47, Gilbert & George, RKD Archive Art & Project, 949

‘What One Finds’

In the almost 300-page inventory of the archive, compiled by RKD archivist Lidy Visser in close consultation with Van Ravesteijn and completed in 2021, the contents are only outlined and the numerous connections are only partially visible. The inventory (literally: ‘what one finds’) is the result of a rational classification of documents, photographs and objects found in the archive (literally: ‘repository’). Only research can reveal the life in art hidden in Art & Project’s 75 m of archive boxes and the connections between the documents. After all, archives without visitors, or rather researchers, are not archives.

The Gallery

The birth of the gallery is documented in the archive by a draft written by Van Ravesteijn in which the name ‘Art & Project’ is mentioned for the first time, accompanied by a floor plan of the gallery’s first location on Wagner Street, the first bulletin sent out and documents relating to the registration of the name Art & Project. Floor plans of the gallery’s successive locations show how the exhibition space expanded with each move. Photographs of both the interiors and exteriors of the galleries on the Van Breestraat, the Willemsparkweg, the Prinsengracht and in Slootdorp, respectively, enliven this image and evoke memories of exhibitions and encounters. Photographs and documents referring to temporary locations do the same thing: in 1970, Van Ravesteijn briefly ran the gallery from Tokyo and also sent several issues of the bulletin from Japan. The gallery also collaborated with MTL in Brussels and with Van Krimpen in Rotterdam. The end of Art & Project is marked by the notarial deeds of the gallery’s closure in 1999 and the numerous and sometimes touching responses to the August 1997 mailshot ‘Ons laatste seizoen’ (our last season), sent from the remote Wieringermeerpolder.

Artists’ Files

The core of the Art & Project archive consists of more than 100 artists’ files, most of which contain correspondence – sometimes business-like, but sometimes also very personal – with artists who exhibited at the gallery, organized projects, proposed exhibitions or publications.5 Some are written or typed letters, others postcards, sometimes accompanied by sketches. The files usually include copies of Van Ravesteijn’s responses, either neatly typed, carefully and clearly worded, on gallery stationery or quickly jotted down in draft form. The most extensive files are those of artists with a long association with the gallery, such as Stanley Brouwn, Ger van Elk, Jan Dibbets, Gilbert & George, Richard Long, Nicholas Pope and Lawrence Weiner. Less large files often also contain a wealth of information on matters major and minor, contacts, reflections, plans and financial issues. In many cases, files include multiple copies of the numerous ephemera and rather less important printed materials that are usually discarded, such as invitations to exhibitions and presentations at home and abroad; they were added to these files as valuable documentation.

Typewriter Art & Project, RKD, Archive Art & Project, 968

The files of artists who never exhibited at Art & Project are also interesting, as they provide an insight into the gallery’s strong international reputation. These files contain numerous project proposals or proposals for the making of Art & Project Bulletins by Vito Acconci, Victor Burgin, Hans Haacke, Robert Mangold, Edward Ruscha and Joel Shapiro, among others. In a separate category is the correspondence with Polish, Japanese and Russian artists who contacted the gallery from their relatively remote worlds. Finally, the rich photographic archive, which contains black-and-white photographs, 35 mm slides and Ektachromes of works that were at one time or another shown and traded at the gallery as well as of other works of art, paint a picture of almost 40 years of gallery history, complemented by photographs of displays at the gallery or at fairs and exhibitions at home and abroad.

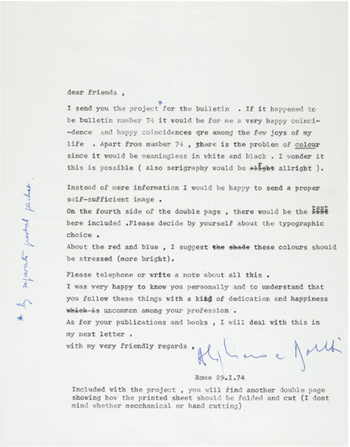

Letter with instructions for an Art & Project Bulletin by Alghiero Boetti (not realized), 29 January 1974, RKD Archive Art & Project, 897

Originals

A very special category consists of originals, ranging from books with commissions by Bas Jan Ader and others, a sheet of pencil sketches by Francesco Clemente, work sent in by James Lee Byars, autographs by Hanne Darboven, a working drawing and sketches by Ger van Elk, sketches by Richard Long and Carel Visser, texts by Peter Struycken and many other, mostly personal messages and postcards.

Realia and Curiosities

If there is one category that demonstrates the gallerists’ extreme attention to detail, it is that of Realia and Curiosities. Number 964 is ‘a long strip of wood used by Sol LeWitt as a tool for the 1971 exhibition’. Number 949 includes several objects, such as the jar of red ink Gilbert & George used to sign their Bulletin 47 in 1971. In the spring of 1972, conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader staged his performance The Boy Who Fell over Niagara Falls at the gallery on the Van Breestraat. Seated in an armchair, he read a story from an issue of the American Reader’s Digest, ‘The Boy Who Fell over Niagara Falls’, about a little boy who ends up in Niagara Falls. Ader periodically took a modest sip of water from a Duralex glass placed on a wicker side table next to him. This glass is stored in the archive under number 958.6 The typewriter used in the gallery was given the number 968. It was, according to the inventory, a birthday present from Adriaan van Ravesteijn’s mother for his twenty-first birthday.

Glass used by Bas Jan Ader during his performance The Boy Who Fell over Niagara Falls, April 1972, RKD Archive Art & Project, 958

Bulletins and Mailshots

Of particular value and interest are the many sketches, drawings and photographs and the correspondence with artists in preparation for the Art & Project Bulletins. The copious cutting and pasting and moving of typographic elements, proofs, clichés and instructions to the printer show the care with which the bulletins were created. Of course the archive contains multiple versions of the bulletins published: unaddressed, addressed to the gallery itself, folded, unfolded, sent and returned copies, and a complete set of the ‘limited edition’ bulletins that were distributed by the 20th Century Art Archives in Cambridge. The many letters received and answered from home and abroad with questions about and requests for missing bulletins illustrate that they were in great (international) demand. Besides the bulletins and all correspondence relating to them, the archive also includes copies of all invitations and mailshots sent, as well as magazine articles, newspaper notices and other publicity messages about the gallery, about exhibitions and relating to interviews with the gallery owners.

Publications

A wide range of publications in the archive illustrates the civic, social and political context of the 1960s, the period in which the gallery was founded: a folder of ‘werkgroep Luns-time is over’, Het Rode Boekje, Atom Club Magazine, seven issues of Provo magazine, the publication In Dienst, published by the Ministry of Defence and the popular youth magazine Hitweek.

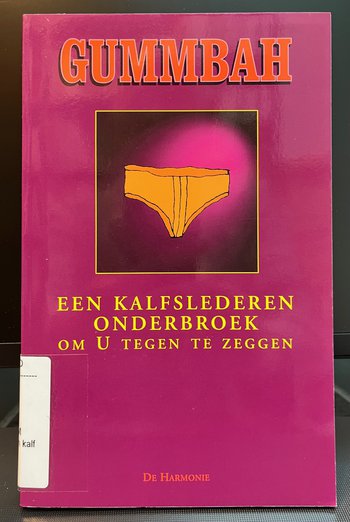

The collection of over 900 artists’ books, art publications and art and other periodicals that are also part of the archive and accessible via the RKD’s library catalogue includes many publications from the 1960s and 1970s, for example a number of cultural magazines such as Randstad, Barbarber, Kreatief and Skrien. In addition to the many specific art and magazine publications, they show Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn’s broad cultural interests. Their sense of absurdist humour comes across through Gummbah’s Een kalfslederen onderbroek om u tegen te zeggen (2013) and the six other books by this cartoonist included in the collection.

Gummbah, Een kalfslederen onderbroek om u tegen te zeggen , Amsterdam 2013, RKD Archive Art & Project, 201703030

Business

Correspondence about acquisitions, loans and works on consignment with numerous museums and galleries at home and abroad, as well as with governments about presentations abroad and subsidy programmes, shows that a gallery is first and foremost a business that requires a great deal of management. The archive contains the complete financial records; the annual reports and accounts and the sales books, arranged by artist, will not be available for consultation until 2061 and 2071 respectively, due to data protection laws. The same applies to the extensive correspondence with individuals and companies who purchased works of art. However, those interested in the consumption and travel habits of gallery owners will be pleased to find inventory number 251: ‘miscellaneous bills and receipts from restaurants and bars’, supplemented by: ‘all train tickets since 1973’. From 1989, for example, all receipts ‘relating to household goods, catering and the like’ have been preserved.

Personal

Both Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn also left personal archives. Van Ravesteijn, who studied at Delft University of Technology for some time, preserved numerous drawings. The archive also contains correspondence with his parents. In 36 personal diaries, dating from 1969 to 2003, we can follow most of his daily activities and appointments. Van Beijeren left records of his work for the Stedelijk Museum and Museum Boymans-van Beuningen and for Museumjournaal. The archive also includes passport photographs, passports, childhood documents and photographs of their first trip together, to Denmark in 1965. Gallery owner Riekje Swart, with whom they maintained very good and close contacts, wrote their horoscopes. Small books, card indexes with addresses and telephone lists provide insight into both personal and business relationships. It is impossible to distinguish between the two. Both men corresponded extensively with friends and acquaintances, including artists and collectors. Postcards received, invitations to exhibitions and publications with commissions, for example from Gerard Reve and his partner Joop Schafthuizen, illustrate the good relations with numerous friends and acquaintances.

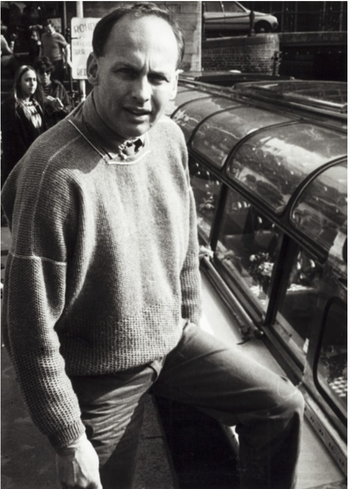

Adriaan van Ravesteijn about to board a canal boat during a trip with Richard Long and his family, undated, RKD, Archive Art & Project, 1363, no. 6

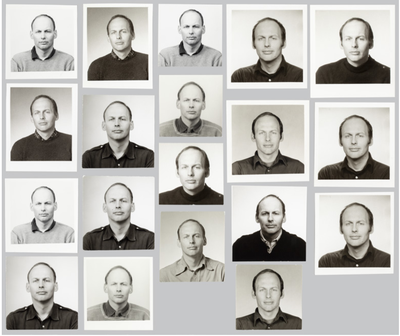

Both snapshots and formal portraits of Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn have survived, taken by Paul Huf and Helena van der Kraan; the archive also includes the passport photographs of Adriaan van Ravesteijn taken by artist Douglas Huebler for his Variable Piece No. 44 / Global (1971).7 Photographs of dinners at restaurant Centraal in Amsterdam with Richard Long, Jan Dibbets, Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Huebler and gallerists Gian Enzo Sperone and Konrad Fischer testify to an informal and friendly atmosphere. Inventory number 1363 includes a picture of Adriaan van Ravesteijn taken on a canal boat during an outing with Richard Long and his wife and children. Photographs of studio visits to, among others, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Andrew Lord, Rinke Nijburg, David Powell, Narcisse Tordoir and many others give an idea of ‘the work of the gallerists’.

Series of passport photos of Adriaan van Ravesteijn photographed by Douglas Huebler for his Variable Piece No. 44 / Global, 1971, RKD, Archive Art & Project, 1030

Finally, the extensive private collection of Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn, called Collection Art & Project /Depot VBVR after their initials, is also extensively documented.

Together with the art collection, which after many considerations and recategorizations is now housed in various Dutch and foreign museums, the archive is the most important legacy of Geert van Beijeren and Adriaan van Ravesteijn: the result of a long life with art.

According to Ulises Carrión, archives are collective creations. In other words, they are not about him, but about all those who have contributed to their formation. Archives are an inexhaustible source of information, kept alive and constantly enriched by connections with other sources and archives. This creates a network of information with ever new users.8

With the completion of the inventory, Art & Project’s archive is not only well preserved and secured, but also ready to come alive.

Notes

1 Artzien. A Monthly Review of Art in Amsterdam 2/8 (June 1980), pp. [10-11]. On Carrión, see: Guy Schraenen et al., Ulises Carrión: Dear Reader: Don’t Read, exh. cat. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía 2017.

2 see Ton Geerts, 'Printing Matters / Art & Project: ‘Documentation Centre with a Sales Section for Books’', in: Jannet de Goede and Lisette Pelsers (ed.), Art & Project: A History, Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum; The Hague: RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History; Rotterdam: nai010 publishers 2023, pp. xxx, or click here

3 Lidy Visser, ‘Inventaris van het archief van Art & Project (1968–2001), 1951–2014; met hiaten’ (RKD: The Hague, 2019), inventory. For the Dutch online version of the archive click here.

4 Sue Breakell, ‘Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive’, Tate Papers 9 (Spring 2008), tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/09/perspectives-negotiating-the-archive (accessed October 2021). On the role and significance of art archives, see: Charles Merewether (ed.), The Archive: Documents of Contemporary Art, London/Cambridge, MA 2006; Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy, Cambridge, MA/London 2008.

5 See, for some good examples: Alied Ottevanger, ‘Dear Adriaan and Geert/Beste Adriaan en Geert: Elf kunstenaarsbrieven uit het archief van Art & Project’, Jong Holland 13/2 (1997), pp. 65-77.

6 See: Paul Andriesse, Bas Jan Ader: Artist/artist (Amsterdam, 1988), pp. 50, 93; Rein Wolfs (ed.), Bas Jan Ader: Please Don’t Leave Me, Rotterdam 2006, pp. 98-99. In 1992, Paul Andriesse in Amsterdam published a book containing a selection of photographs of this performance at Art & Project.

7 The work is from the Art & Project /Depot VBVR collection and now part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, inv. no. 1039.2007.1

8 Javier Maderuelo, ‘An Archive Is an Archive Is an Archive’, in: Schraenen et al., Ulises Carrión, op. cit. (note 1), pp. 57-59.