Interview with Adriaan van Ravesteijn on the Art & Project Bulletins, May 17, 2011

Original interview in Dutch, (and translated) by Ton Geerts

Published in:

Louisa Riley-Smith, Art & Project Bulletins 1-156. September 1968-November 1989, Rennes 2011, pp. 63-84

TG: In the early Bulletins you stated that “Art & Project plans to bring you together with the ideas of artists, architects and technicians to discover an intelligent form for your living and working space. Art & Project invites you to participate in its exhibitions which will explore ways in which art, architecture and technology can combine with your own ideas.” Were you optimistic at that time in this new form of participation?

AVR: Yes we were actually. When I met Geert in 1965 he was already into the arts. He had an interesting art collection and I had a few works myself, did things in the arts in my own way and was still studying architecture at Delft University. Since 1966 Geert worked in the Stedelijk Museum, first in the library, later as curator in the department of painting and sculpture.

In 1979 he left the museum, and began to work full time for Art & Project.

While in the library he selected the documentation for the catalogue of the “Op losse schroeven” exhibition in 1969. In those days Europe was in full excitement and in 1968 everything changed. The anti-establishment movement took over and the participation of the public became important in the realization of the art work. It was all in the air at that time when we started Art & Project in 1968 on the ground-floor in a residential area far from the Amsterdam city centre. We just wanted to make interesting exhibitions, and we mailed invitations so people would visit us and perhaps we could make a profit in case of a sale.

Although I believed that one could merge art and architecture – I still had a few contacts in Delft that were interesting enough to maintain – the first real participation with architects and designers did not really work out, except with for example Paul Schuitema and Aldo van den Nieuwelaar (Bulletin 5), and of course in our first show we made with the artist Charlotte Posenenske when you could simply take the sculptural building elements and make your own structure at home.

TG: Why did this first statement disappear in the later Bulletins?

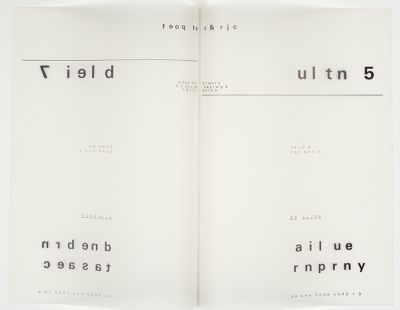

AVR: We did indeed remove the statement in Bulletin 3. It was a natural process, not a tragedy. In Bulletin 2 it was of course still relevant because of the architectural aspects of the work of Slothouber and Graatsma. They made for example, as well as furniture, small architectural forms as multiples that could be used in various ways, and in a certain way also became art. Gradually we moved towards conceptual art. In Bulletin 7, we asked people to contact Art & Project if they had any suggestions for enriching our “silly” garden. It was Stanley Brouwn who introduced with Bulletin 8 this “new art”. Geert had met him in the library of the Stedelijk Museum. We were not disappointed with the architects but there were so many new interesting forms of art. Times were changing and we shifted gradually towards conceptual art.

Stanley Brouwn en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #8, 1969

Den Haag, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: In an interview with Christophe Cherix you said that the Bulletins were the spinal column in the history of Art & Project, because their appearance never changed. How did the idea for the Bulletin develop?

AVR: There were all kinds of interesting and cheap possibilities to make printed matter in those days. A lot of movements of 1968 produced many simple and cheap sheets with political messages and all kinds of propaganda. We did not want to make a “classic invitation” with just the name of the artists and not many galleries used pamphlets like we did. Because we were not situated in the city centre of Amsterdam, we were convinced that we had to give more information on our exhibitions hoping to get more visitors. Due to the many contacts with artists we soon understood that the Bulletin could comprehend the entire exhibition. For example Bulletin 10 by Lawrence Weiner.

Someone like Seth Siegelaub of course changed the way art was presented. Those ideas were very inspiring. The gallery was no longer a building with a classic shop front but could be situated everywhere and it could really change places in very different ways. We started having a small space at my parents’ home. In 1970 when I went for two months to Japan I temporarily changed the address of the gallery to an address in Tokyo. That was quite easy!

Lawrence Weiner en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #10, 1969

Den Haag, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: How did the strong typographic element of the Bulletin develop?

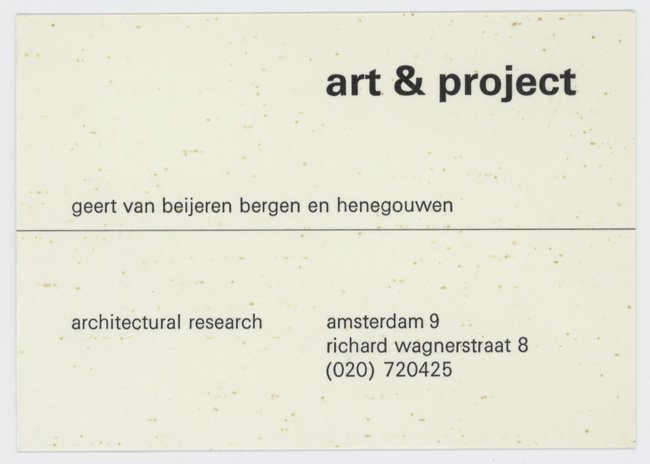

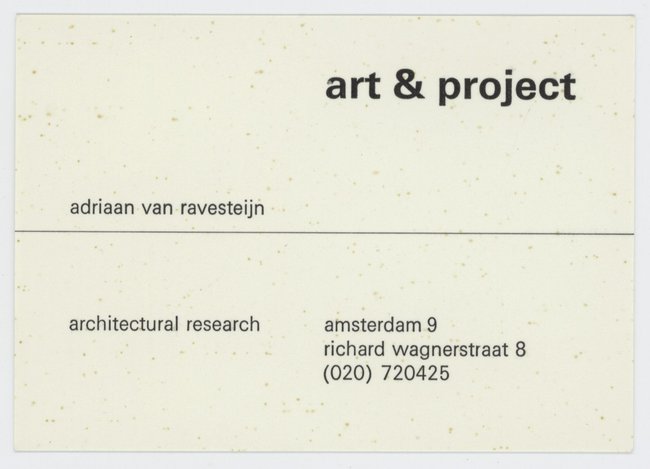

AVR: We already had headed letter-paper and a business card at the start, designed by graphic designer Ton Raateland. We did not want to use the word “gallery” because that was passé in those days. Instead of a glossy announcement we chose a simple leaflet. I used the basic design of the headed paper by Raateland for the design of the Bulletin. So I put the words “art & project” and “architectural research” on the right side of the paper. After folding the Bulletin into thirds, I put the address on the leaflet with my RENA system (an early mimeograph addressing system) and the Bulletin could be posted. That turned out to be a mistake because the postal services thought that the Art & Project address on the right was that of the receiver and many Bulletins were sent back to us. So I did change the layout from Bulletin 3, with our gallery name and address on the left side.

To maintain the simple layout was also a form of laziness. Why change? If you don’t want to rethink and consider each following Bulletin. Some small changes were made eventually because I made the typographic elements myself using transfer lettering characters and according to the designer of the headed paper, I did not space them too well. Also the printer could not find our original ampersand sign so they had to use another sign, as long as it matched with the Univers typefont. The designer was not so happy. I had not consulted him about these alterations, but we just started the gallery and had to be practical at a very low-budget.

Business card Geert van Beijeren, c. 1968

Business card Adriaan van Ravesteijn, c. 1968

TG: The Bulletins had an international audience. Dibbets (Bulletin 15) mapped this international element in late 1969. Bulletins could be sent from Amsterdam as well as from Düsseldorf or Tokyo. To whom did you send the Bulletin?

AVR: First we send to people we knew through our contacts in the gallery-world, specially of our good friend Riekje Swart, who had a gallery in Amsterdam. Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk exhibited in her gallery. Geert of course had many contacts at the Stedelijk Museum and we soon got requests from all over the world to send a Bulletin. The magic of the Bulletin was the fact that we numbered them. Regular mailings without a number were easily thrown away, but when people see a number they want to collect. I began to number the Bulletins because I like order. Also it is a sign of optimism: No.1 is the start of something new!

Jan Dibbets en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #15, 1969

Den Haag, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: As American artists began to play an important role in Conceptual art, how did Lawrence Weiner for example come to be included?

AVR: Weiner we met in Amsterdam as participant of “Op losse schroeven” and artists like Ger van Elk and Jan Dibbets knew many artists and they were our main contacts with conceptual artists. We showed their works and it was of course important to them to maintain and raise the quality of the gallery. They introduced us to new interesting artists. Van Elk introduced Gilbert & George to our gallery and his Californian friends Bas Jan Ader and Allen Ruppersberg. Dibbets connected us with Sol LeWitt and Joseph Kosuth. Many galleries functioned that way. Van Elk and Dibbets were in the centre of an interesting network, so the gallery could actually feed itself.

TG: Did you approach artists and ask them to make a Bulletin or did the artists approach you? And of course were there any reasons not to make some Bulletins with artists?

AVR: We invited the artists, but artists also contacted us for an exhibition.

In the beginning every exhibiting artist made a Bulletin. Until 1973 we were located in small spaces and we needed the Bulletin to communicate. With our move to the Willemsparkweg we got much more space. The first painters and sculptors joined the gallery and we became a more traditional gallery. That was a turning point; since then, not every artist made a Bulletin and we sent often only an invitation leaflet, a single sheet, a sort of half Bulletin.

Later also invitation-cards with a picture. Those invitations are less well known. Next to our old generation (Weiner, Long and Gilbert & George) were our new generation artists, Clemente, Cucchi and Chia, who also used the Bulletins.

Not all the artists were “Bulletin artists”. Someone like the Dutch painter Ben Akkerman was not interested in making one. But Toon Verhoef made a collage of paintings, not merely a reproduction of his work (Bulletin 126). Several times, we sent a Bulletin with a photographic interior shot of the ongoing exhibition (ie: Tony Cragg, Bulletin 141). I was in a hurry getting it printed so people could receive the Bulletin halfway before the end of the exhibition. Don’t forget we are in the years before e-mail and Internet!

Toon Verhoef (1946-) en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #126, 1981

Den Haag, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: Did some artists make several Bulletins?

AVR: Yes, many artists, and that was essential to the function of the Bulletin. Richard Long for example often suggested to make a new Bulletin and mostly not in relation with an exhibition. He used the Bulletin as a separate element of his work. Stanley Brouwn also worked that way. In the “inventory of the Bulletins” we published in 1997 you can read which Bulletins accompanied an exhibition, and which not. Daniel Buren for instance claimed two Bulletins in a row. For his March 1974 exhibition he made one on transparent paper (Bulletin 75). For the exhibition he fixed sheets with white and transparent strips on the windows, so the sunlight showed only the shadows of the non-transparent stripes on the walls and floor of the further empty gallery. To document this exhibition he reserved the following Bulletin 76, to be published later, as a photo souvenir to the 1974 exhibition. The Bulletin came out two years later in 1976. In the meantime already two following Bulletins were published. In that in-between period people often wrote and telephoned and asked me to send Bulletin 76, worried that it was lost in the mail. So Buren, Long and Weiner liked the Bulletin as a creative medium. For others it didn’t work out, they could better use a traditional invitation.

Daniël Buren and published by Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #75, 1974

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: How about the famous Bulletin 24 by Daniel Buren?

AVR: We invited Buren to make an exhibition and he very much liked also to do something with the medium of the Bulletin. We paid him a visit in Paris in the summer of 1970, and came back home with the exhibition, a “pile” of sheets, printed with yellow and white stripes.

According to Buren’s instructions, we pasted these sheets during five consecutive days on five different outdoor locations near our gallery in Richard Wagnerstraat. In small adverts in the Dutch morning paper “De Volkskrant” we announced the next day where the white and yellow stripes we installed the previous day were visible. The last location was outside the entrance of the gallery, so in the last advert, we “revealed” who was behind the work.

Also according to Buren’s instructions, the Bulletin that accompanied this exhibition, number 24, never should be published. A year later the collector Herman Daled contacted us to make a Bulletin. It became Bulletin 45 “a private collector”. In this Bulletin Daled presents anonymously the twelve paintings he acquired in 1970, one each month. Buren’s name is not mentioned in the Bulletin, but it is very clear that he is the painter. Since we knew that Herman Daled and Daniel Buren were friendly, we felt free to recognize this Bulletin as authorized by Buren.

Anoniem 1971 en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #45, 1971

Den Haag, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

TG: Some Bulletins were displayed as objects or conceptual works of art. In the MoMA exhibition “Information” in 1970 and again at the Cologne Art Fair in 1972. What were the main reasons for showing the Bulletins? Was it a way of communicating about the artists and the gallery?

AVR: Yes of course. After New York in 1970 which exhibited all the Bulletins published at that time, we did the same in 1972 at the Cologne Art Fair with all the 60 Bulletins issued by then. Simultaneously we issued a catalogue of those first 60 Bulletins. To exhibit these Bulletins at an art fair was quite unusual. Most galleries at a fair save the walls for saleable works. We showed next to the Bulletins a few authentic artworks, which were reproduced in a Bulletin, for example a work by Robert Barry (Bulletin 37), the original photograph of “A Touch of Blossom” by Gilbert & George (Bulletin 47) and Sol LeWitt’s drawings in Bulletin 60.

TG: You also presented Stanley Brouwn at “Prospekt 69”. Was his Bulletin 11 there already on show?

AVR: No, not the Bulletin itself. The inside-text of this Bulletin was typewritten and fixed on a small piece of plywood, hung free from the ceiling in the middle of the room. The text read: “walk during a few moments very consciously in a certain direction;simultaneously an infinite number of living creatures in the universe are moving in an infinite number of directions.” We mailed the Bulletin from Düsseldorf, on the day of the opening of “Prospekt 69”.

TG: How did you make a Bulletin and does the archive in the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History) still house the originals?

AVR: Not all the originals, authentic art work went to various collections. But somewhere in the RKD are all the sketches, photos, notes and further correspondence from and with the artists about the design of their Bulletin. Plus the typewriter I always used and my Japanese bamboo ruler, great help with the folding of the Bulletins.

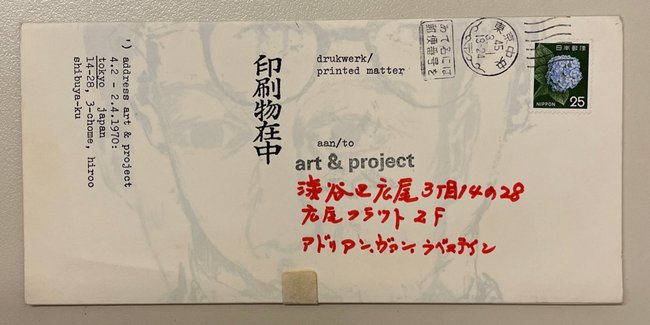

For Bulletin 20 Gilbert & George sent me in late 1969 the photographs of two drawings, “George by Gilbert” and “Gilbert by George” to be printed in Tokyo, where Art & Project settled down for two months, early in spring 1970. The Bulletin was mailed from Japan. The etching plate for this Bulletin is still in the archive in The Hague.

From the same printer we also made Bulletin 21 of Yutaka Matsuzawa. I didn’t know him before I came to Japan and we both were happy to produce and mail the Bulletin at such short notice.

The drawings “George by Gilbert” and “Gilbert by George” we showed later that year in their first exhibition at Art & Project.

In the archive there is also an explanation-drawing Richard Long sent together with the photo and the text for his Bulletin 35 “Reflections in the Little Pigeon River, Great Smoky Mountains, Tennessee”. He used a previous Bulletin (Lawrence Weiner Bulletin 10) for the drawing. Certainly because the centre spread was almost blank! More artists used a previous “empty” Bulletin to present their wishes.

I always prepared the first page of the Bulletin myself and then went to The Hague to discuss with the printer the inside, and give him the drawings, photographs and /or the text. Nothing could really go wrong and there were never any problems.

Sometimes I got special instructions. Gilbert & George for example did not want their name in large on the front page. Instead they signed Bulletin 73 with an embossed stamp and each copy of Bulletin 47 (“A Touch of Blossom”) with red ink. The inkwell with the red ink is still kept in the archive. I am afraid it will have desiccated by now.

Also, the Bulletins were sent from Düsseldorf and Tokyo. Jan Dibbets’ Bulletin 56 was mailed from Venice in occasion of his presentation at the Dutch Pavilion Biennale 1972. I remember specially the folding of the Bulletins as a difficult job because of the specific folding this Bulletin required. The horizon line on the land and seascape photo on the inside page was measured according to the sectio aurea (golden ratio). To not disturb the balance on the inside of the Bulletin, we decided that the folds should also follow the sectio aurea.

Our room in Venice was bloody hot and the folding demanded a lot of concentration. Due to the very slow delivery of the Italian post in those days (up to three weeks for an ordinary postcard), no one responded when I was already long back in Amsterdam.

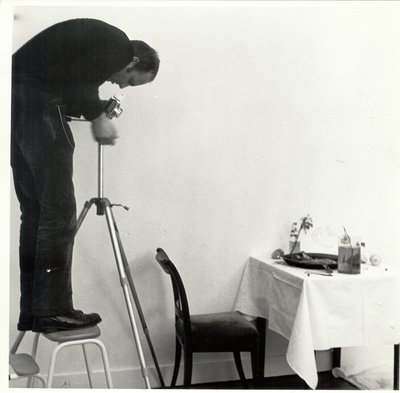

TG: Did you see the photograph of you in Ger van Elk’s home, taking a photograph?

AVR: Yes I remember that Ger van Elk took that one while I was making one of the eight slides for his work Paul Klee – Um den Fisch, 1926, presented in Bulletin 33. I also made a photo in Marken for his famous Co-founder of the word OK. We bought at a local butcher that very large look alike of a smoked sausage, but it was more a liverwurst. Later, van Elk used the same sausage for an OK-work on another location. For the time in between the works this sausage was stored in the boot of his car.

Adriaan van Ravesteijn making a photo of Ger van Elk's Um den Fisch; photo by Ger van Elk, Archive Art & Project, nr. 1363, 2

TG: How did people respond to the Bulletins?

AVR: From our start in 1968, we immediately had enthusiastic reactions, receiving letters from all over the world. We called it fan mail.

Also the response to Bulletin 14 Jan Dibbets (1969), in which we asked the recipient to return to Art & Project the right-side of the Bulletin, was overwhelming.

On three individual maps, Holland, Europe and The World, we indicated with drawn lines the places from where all these returned single sheets came. We showed these three maps in the gallery.

TG: Were the Bulletins already collectors’ items by then?

AVR: Yes, that happened pretty fast. Collectors requested us if any of the previous Bulletins were still available. We stopped sending them when we realized that our stock was shrinking too fast. But today, people still send me lists with missing Bulletins. Here again it is the magic of the numbers. Some Bulletins are of course still available on the antiquarian market. Sometimes with the addresses and names of the former owners who had received them. Interesting for me to know who sold them!

Over the years, people often asked us why not publish a book, with all the Bulletins reproduced. We however categorically refused this option. In printing, turning the pages and being forced to follow the Bulletins from 1 to 156, kills the pleasure to see and touch each Bulletin individually.

Together with Louisa Riley-Smith of 20th Century Art Archives, we found in 1997 an ideal compromise. Using the Bulletins still available in our original stock, we could, with only nine reprints, realize two editions of 25 complete sets, with seven reprints in each set.

For exhibition purposes, one original set is in the collection of the MoMA, New York.

In 2009, it was part of the exhibition “In & Out of Amsterdam: Travels in Conceptual Art, 1960 –1976”, curated by Christophe Cherix.

Before, this set had been exhibited in Rotterdam (Art & Project / Van Krimpen), Ljubljana (print-biennale), Geneva (Mamco) and Paris (Cneai).

TG: And then in 1989 it stopped with Bulletin 156.

AVR: Yes. When we left Amsterdam in January 1990 and went to Slootdorp, in the middle of nowhere, 60 km up north. That was the end of the Bulletins. It also was a farewell to Amsterdam and the active art world. But it turned out to be not the end and we began to work in Slootdorp with young artists, a new generation of painters, like Hans Broek and Koen Vermeule.

TG: I do believe there is a Bulletin 157?

AVR: Yes there is! Around the time we stopped with Art & Project, our sculptor Leo Vroegindeweij took the initiative to make this Bulletin in an edition of only two, of which one is framed. He asked several of “our” artists to make a contribution. But this time we had nothing to do with this Bulletin, although it was printed at our original printer in The Hague.