Printing Matters / Art & Project: ‘Documentation Centre with a Sales Section for Books’

Ton Geerts

From 1969 to 1991, Geert van Beijeren and Adriaan van Ravesteijn collected more than 900 artists’ publications, most of them by conceptual artists. These publications now form part of the extensive Art & Project archive, accommodated by the RKD, Netherlands Institute for Art History.1 In addition to the Art & Project Bulletins, which brought the gallery international fame, the collection includes some 30 books published by the gallery.2

Conceptual Art and Artists’ Books

Artists’ books are, like any other medium, a means of conveying art ideas from the artist to the viewer/reader. Unlike most other media they are available to all at a low cost. They do not need a special place to be seen. They are not valuable except for the ideas they contain.3

Sol LeWitt

From the mid-1960s, the artist’s book as a means for an artist to disseminate, record or document ideas grew increasingly popular.4 Conceptual artists such as Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Robert Barry and Joseph Kosuth in particular made frequent use of the medium. They defined their art as ‘idea art’, sometimes bound by strict rules.3 They worked with abstract concepts such as time, perception, energy or ‘thinking’. Barry, for example, photographed disappearing, invisible gases in certain spaces, played with language in his project during the exhibition the gallery will be closed, and focused on the subconscious in his publication All the things I know but of which I am not at the moment thinking – 1:36 PM; June 15, 1969.4 By considering the actual execution of concepts into material works of art as secondary, these artists ‘dematerialize’ art. The formulated ideas or concepts know no boundaries and can be communicated relatively easily.

Artists’ publications, which come in many shapes and sizes, are an attractive medium for the marketing of ideas.5 They can be produced cheaply, for example using a photocopier, their distribution is relatively simple and, because of the often large print runs, the books are in principle accessible to a wide audience, without the intervention of the commercial art circuit, the so-called poengalerieën (cash-cow galleries).8 The idea is that art is no longer exclusive.

During the 1960s, going with the tide of civic, political and economic change, these new interpretations of art and the art business became more prevalent. And although many conceptual works of art are actually executed in practice, the image of conceptual art is still strongly defined by this focus on the ‘dematerialized’.6

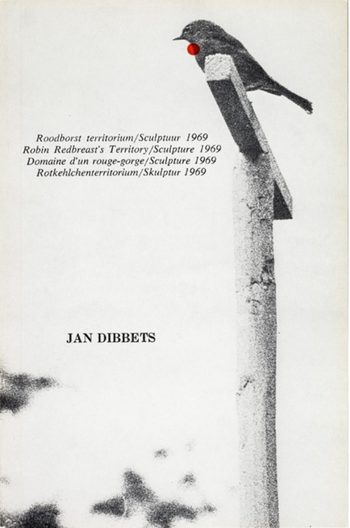

One of the pioneers and publishers of conceptual artists’ publications was the American Seth Siegelaub (1941–2013).7 He was one of the first to distinguish between the book as a primary source of information and the book as a secondary source of documentation or information. In the first instance, the publication is the work: the work of art can only be recorded in the form of a document. A good example of this is Jan Dibbets’ Roodborst territorium/Sculptuur 1969, published by Siegelaub in 1969 (Fig. 1).8 Dibbets, one of the leading Art & Project artists, wanted to turn the flight pattern of a robin in Amsterdam’s Vondelpark into a sculpture. But a bird can never perform all of these movements in one flight, so Dibbets needed a booklet to document its movements.

Fig.1: Jan Dibbets, Roodborst territorium/sculptuur 1969, april-juni , New York, Köln 1970

A book as a secondary source of information involves the documentation of, for example, a performance or an action. Photographs, sketches, texts and other documentation are bundled into a publication to give ‘the reader’ an idea of the work of art. Such publications often look more like traditional catalogues than like artists’ books.

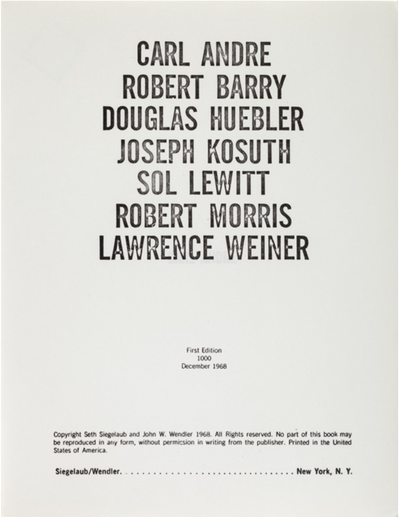

In some cases it is difficult to distinguish between primary and secondary documentation and information: Lawrence Weiner initially regarded the texts he included in his book Statements (1968) as descriptions of works, that is, as secondary information, but later referred to these descriptions as the works themselves, that is, primary information. Even with regard to Siegelaub’s own Xerox Book (1968), a ‘group exhibition’ in the form of a book, it is not easy to draw sharp boundaries. The publication contains works created on a photocopier (xerox machine) by Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris and Lawrence Weiner (Fig. 2).9 Siegelaub’s Xerox Book shatters the classical exhibition model. He believed that printed media, including artists’ books, were a better means of communicating art than traditional exhibitions. He was therefore convinced that the exhibition in book form would outlive the traditional exhibition.

Fig.2: Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol Lewitt, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner [Xerox Book] / editor Seth Siegelaub. - New York 1968

Art & Project Bulletin

When Art & Project was founded in 1968, Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn decided to send out a bulletin to inform interested parties about the activities of the gallery.10 The bulletin was invariably a folded sheet of A3 paper and the typography was always almost identical. The first seven issues still focused on the relationship between art and architecture, the gallery’s initial area of interest, but when conceptual artists began to join Art & Project, the character of the bulletin changed. From Bulletin 8 onwards, there was room to develop ideas for works of art, starting with a contribution by Stanley Brouwn, followed by Jan Dibbets, Bernd Lohaus and Ed Sommer. The first truly separate ‘conceptual’ artist’s bulletin was Bulletin 10 (1969) by Lawrence Weiner. This issue only includes three lines of text by the artist: a translation from one language to another / een vertaling van de ene taal in de andere / une traduction d’une langue en une autre. Weiner did not use the inside of the A3 sheet. Bulletin 10 is also the first bulletin that was not accompanied by a physical exhibition at the Art & Project gallery. The publication was independent, a conceptual work of art and an exhibition in one.

From 1969 to 1972, Weiner’s radical gesture was followed by a series of issues with original work by Weiner himself, Stanley Brouwn, Joseph Kosuth, Robert Barry, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, Jan Dibbets, Ger van Elk, Gilbert & George, Douglas Huebler, Ian Wilson, Daniel Buren, Mel Bochner, Hanne Darboven and others. They used the bulletin as a medium for the dissemination or documentation of their ideas, turning it into a work of art and sometimes even an exhibition: the bulletin model became an innovative alternative to the classic gallery model.

Through the global distribution of the Art & Project Bulletin, the gallery was able to reach a considerable network of artists, collectors and enthusiasts, and to gain an international reputation. The continuous numbering of the bulletin also proved successful: they soon became collector’s items, part of a sought-after series, of which no issue should be missed.11

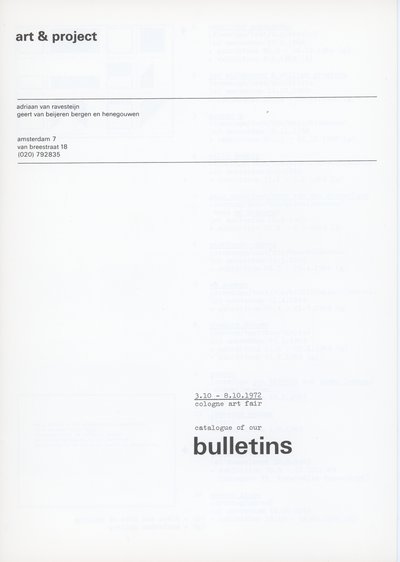

The fact that the bulletin was considered a serious artist’s publication was already apparent at the first American museum exhibition on conceptual art, Information, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970, which displayed all of the Art & Project Bulletins published up to that time. The catalogue of the exhibition looks like an artist’s publication, bundling a collection of conceptual artist’s pages (documents, texts by artists, photographs, blank pages); this makes the book distinctly different from the classic catalogue with explanatory texts and images of the works of art on display. The page dedicated to Art & Project only contains a reproduction of Bulletin 21, by Japanese artist Yutaka Matsuzawa. Further presentations of the bulletins followed relatively quickly, including ones in Cologne, Poznan and Tokyo.12 The catalogue of the first 62 issues published was presented at the 1972 Kölner Kunstmarkt (Fig. 3). Here, too, documenting was considered an essential aspect of conceptual art. In late 1972, the exhibition Kunst als boek at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam displayed ten Art & Project Bulletins alongside other artists’ publications.13

Fig. 3 Catalogue of Art & Project Bulletins, 1972

Fig. 4 Lawrence Weiner, Perhaps when removed / misschien door verwijdering, Amsterdam: Art & Project, January 1971, first printing

Artists’ Publications

In addition to 156 bulletins, Art & Project published over 30 artists’ books between 1968 and 1989. The first one appeared in 1971: Lawrence Weiner’s Perhaps when removed / Misschien door verwijdering, followed shortly afterwards by From along a Riverbank by Richard Long (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Both publications have the same small oblong size of 21 × 10 cm. The design is austere, the print run only 300 copies.14

Perhaps when removed, one of Weiner’s first works of book art, consists of 20 unnumbered pages and contains a series of his texts. Language is the material from which Weiner creates his images; the materialization of his work took place through words and texts, which he applied to walls and displayed in books, among other things. Weiner believed that the typographical execution, the layout, required extreme precision. He published countless artists’ books and also considered many of his publications to be exhibitions. His reasoning was that if the public would not come to the exhibition, the exhibition would have to come to the public.15

Long’s From along a Riverbank has the same number of pages and contains 15 images of tree leaves that he collected along the banks of the River Avon – black-and-white reproductions of the real leaves that make up the work of the same name that is in the collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum.16 For Long, the artist’s book was a means of documenting interventions in often remote landscapes, but he also considered the publications themselves to be sculptures.17

Fig. 5 Richard Long, From along a Riverbank, Amsterdam: Art & Project, August 1971; first printing

Fig. 6: Richard Long, From Around a Lake, Amsterdam: Art & Project, March 1975, 2nd edition

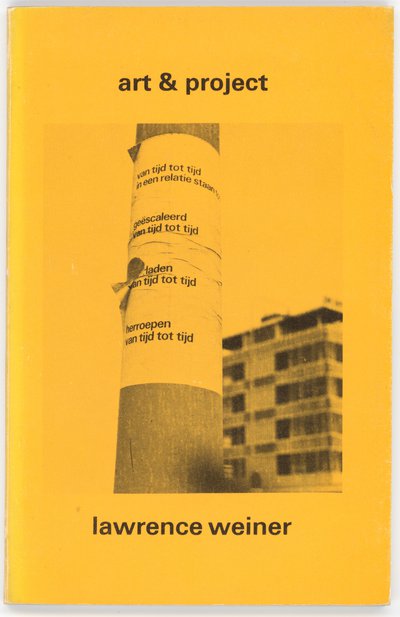

Fig. 7 Lawrence Weiner, Having from time to time / a relation to: […], Amsterdam: Art & Project, March 1976

Following Weiner and Long’s publications, a series of similar small, simple booklets appeared in a short period of time. In 1972, one with five works by Ger van Elk from 1969–1971: The Well Shaven Cactus, Paul Klee – Um den Fisch, 1926, The Co-Founder of the Word O.K., The Discovery of the Sardines and The Symmetry of Diplomacy. The publication only includes images of the works, there are no explanatory notes and once again the print run was 300 copies. One year later, three booklets containing work by Yutaka Matsuzawa and again Long and Weiner were published, followed in 1974 by a booklet containing texts and images by Robert Barry. Two more publications of the same size appeared in 1975 and 1976: Long’s From Around a Lake (a second edition published in response to some irregularities in the 1973 first edition) and Having from time to time / a relation to by Weiner (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7).

Art & Project produced two publications by Stanley Brouwn, with whom the gallery had worked from the start, in accordance with Brouwn’s own uniform design rules. In 1972, the 268-page publication 1 step-100000 steps appeared in collaboration with the Utrechtse Kring, a group of Utrecht art history students supervised by Carel Blotkamp and Frans Haks, to accompany an exhibition of Brouwn’s work in the Neudeflat in Utrecht.18 In 1978, Art & Project published the booklet 1000 mm 879 mm in the familiar Brouwn layout of 15 × 15 cm, in a print run of 1,000 copies. The publications share their austerity and minimalism with other Art & Project publications by conceptual artists.

From the mid-1960s, the production of artists’ publications, especially conceptual artists’ publications, became increasingly popular. Besides Art & Project, related galleries such as Leo Castelli (New York), Yvon Lambert (Paris), Sperone (Turin) and Konrad Fischer (Düsseldorf) also produced artists’ books. Although their production was relatively cheap, artists still often turned to their gallery or a publisher to finance an entire print run.19 However the intended ‘democratic’ character of artists’ books (cheap and produced in high numbers, and therefore accessible to ‘everyone’) turned out to be largely an illusion. In practice, as critic Lucy Lippard observed, artists’ books mainly aroused the interest of a small group of enthusiasts.20

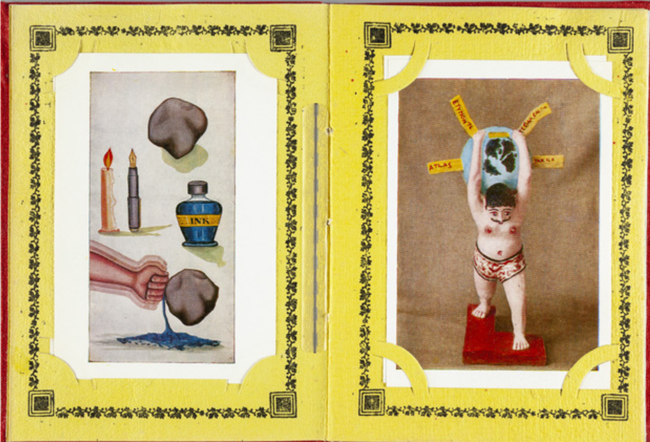

By the end of the 1970s, the role of conceptual art seemed to have been largely played out. Art & Project increasingly focused on other forms of visual art, initially on the Italian Transavantgarde of artists such as Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia and Enzo Cucchi in particular. With Clemente and Cucchi, the gallery produced not only a series of bulletins, but also two artists’ books. With Clemente, the booklet Undae Clemente Flamina Pulsae was printed in India with a stated edition of 800 copies (Fig. 8). In reality, the print run was lower: to avoid problems with customs, only 400 copies were eventually printed and sent out.21 Cucchi’s publication was produced in collaboration with the Paul Maenz Gallery in Cologne. The Italian Salvo’s book Della Pittura (1980) was also a co-production, this time by Art & Project, Barbara Gladstone, Paul Maenz and Massino Minini (Fig. 9). Each of these new publications has its own, non-uniform design. The same goes for the artists’ publications by Leo Vroegindeweij (1980) and Ab van Hanegem (1993), and for David Tremlett’s artist’s book Ruin, which the gallery published in 1987.

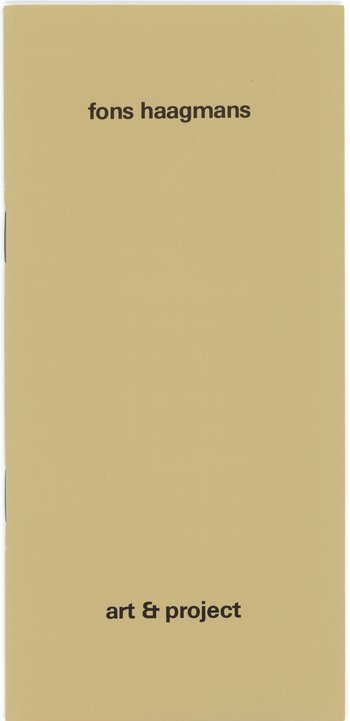

Interestingly, from 1990 to 1997 – the final issue of the Art & Project Bulletins was published in 1989 – the gallery published eight booklets in the small, oblong size of the early years. They contain images of works by Peter Struycken, Emo Verkerk, Fons Haagmans, Lawrence Weiner, Nicholas Pope, Joris Geurts and Han Schuil, respectively (Fig. 10). Only Weiner’s booklet is a true artist’s publication; the others can be considered small exhibition catalogues. The typography is identical to that of the first series; Pope’s and Schuil’s publications have dark- and light-blue covers, respectively. That of Geurts is dark grey, Haagmans’ is light brown. The other booklets have white covers, like the 1970s publications.

Fig. 8 Francesco Clemente, Undae Clemente Flamina Pulsae, Amsterdam: Art & Project 1978

Fig. 9 Salvo, Della Pittura / On Painting / Über die Malerei (hrsg./ed. Paul Maenz & Gerd de Vries), Köln: Buchhandlung Walther König 1986; [coproduction of Art & Project, Amsterdam; Barbara Gladstone, New York; Paul Maenz, Köln; Massimo Minini, Brescia]

Fig. 10 Fons Haagmans, Schön ist die Jugend, Slootdorp: Art & Project, May 1991

Ephemera: Ephemeral Printed Matter

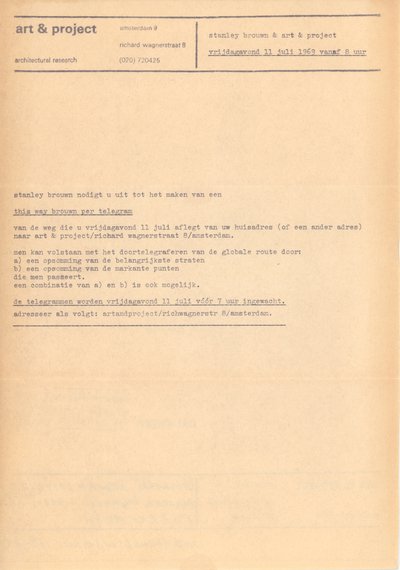

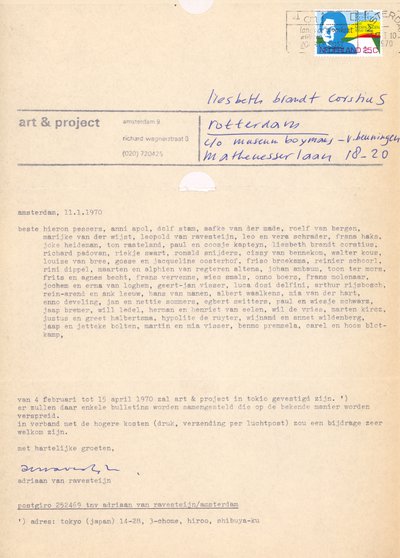

Although the bulletin remained the gallery’s main means of communication for a long time, Art & Project also sent out ‘regular’ invitations or ‘mailshots’. Between 1969 and 1998, the last year of the gallery’s existence, it sent out hundreds of invitations and announcements on A4-size paper and of a typography and design similar to that of the bulletins until the early 1980s, and in a great variety of sizes and colour schemes after that. Initially the mailshots were mainly meant to keep Dutch contacts informed about the gallery’s exhibitions and other activities. The first invitation, sent on 11 July 1969, already looked exceptional: it was an invitation from Stanley Brouwn ‘to make a this way brouwn by telegram’. This invitation contains instructions for the invitees. They are asked to forward the global route between their home address and the gallery address by telegram on the day of the opening (Fig. 11). Other mailshots contain more generic announcements. A mailshot dated 11 January 1970, for example, announces the temporary relocation of the gallery to Tokyo, from where Van Ravesteijn will run it: ‘From 4 February to 15 April 1970, Art & Project will be located in Tokyo . . .’ (Fig. 12) Yet another mailshot announces that Gilbert & George will be performing as living statues on 12 May 1970 at 8 p.m.

Fig. 11 Stanley Brouwn nodigt u uit tot het maken van een this way brouwn per telegram […], 11.7 1969

Fig. 12 Van 4 februari tot 15 april 1970 zal art & project in tokio gevestigd zijn [...] er zullen daar enkele bulletins worden samengesteld die op de bekende manier worden verspreid / in verband met de hoge kosten [...] zou een bijdrage zeer welkom zijn [...], 12.1 1970

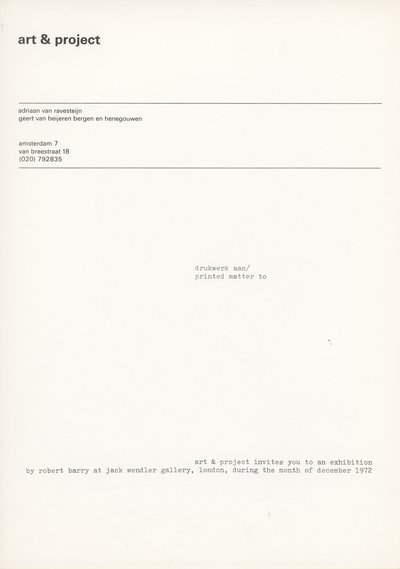

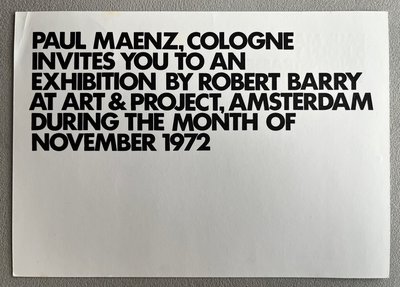

Fig. 13 Art & Project invites you to an exhibition by Robert Barry at Jack Wendler Gallery, London, during the month of december 1972, Art & Project invitation 1972

In 1972, the gallery sent out an invitation saying: ‘Art & Project invites you to an exhibition by Robert Barry at Jack Wendler Gallery, London . . .’ (Fig. 13) This invitation is the second in a series, sent to members of the European network of galleries representing Barry. This is Invitation Piece by Barry, consisting of nothing but the invitations sent. The series was started by Paul Maenz in Cologne, inviting people to come to Art & Project, and ended there as well (Fig. 14). The fact that Art & Project’s invitations transcended the ‘regular’ character of invitations is also evident in two mailshots from 1973 and 1974, sent on the occasion of joint presentations by Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, at Art & Project and gallery MTL in Brussels. The invitations, formatted like the bulletins, contained artistic contributions by LeWitt and Darboven on the inside.

Invitations, mailshots and other ‘ephemeral printed matter’ are increasingly seen as important historical material that contains a lot of information about the ways in which galleries as well as artists communicate.22 Such printed matter is often carelessly discarded. However, the archives of Art & Project are a rich source of carefully preserved ephemera, also from other galleries, museums and artists.

Fig. 14 Paul Maenz invitation for an Art & Project exhibition by Robert Barry, 1972

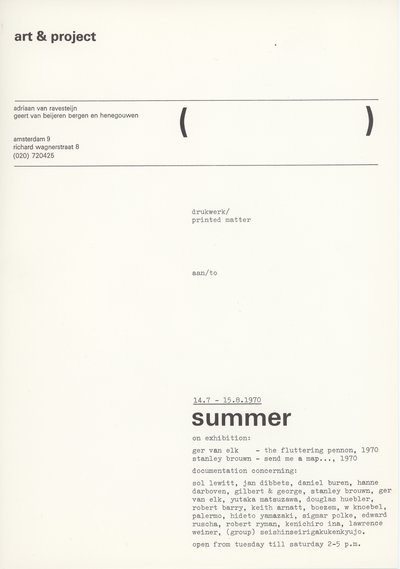

Fig. 15 Invitation for the Summer exhibition 1970

Fig. 16 Advertisment;The first of eight books we published since 1971

Art Rite (winter 1976/1977) no. 14, p. 53

A ‘Documentation Centre with a Sales Section for Books’

Those same archives also contain a letter from Van Ravesteijn to De Nederlandsche Bank dated 14 May 1971.23 The letter sheds some unexpected light on the way the gallery is run:

Art & Project organizes exhibitions of the work of modern visual artists from the Netherlands and abroad. In addition, Art & Project is a documentation centre with a sales section for books, catalogues and other publications about these artists. Many of our international contacts are concentrated in the USA and in order to simplify the buying and selling of publications and the like to and from this country, I request your permission to open a dollar account at the Algemene Bank Nederland in New York. The estimated annual turnover through this account is between $300 and $500.

Here, Van Ravesteijn not only characterizes Art & Project as an exhibition space for modern art, which it obviously was, but also and explicitly as a documentation centre with a sales section for publications. Indeed, it was precisely for the benefit of the latter activity that he required a dollar account in New York. The role that documentation played in the gallery was probably to some extent due to its cramped quarters in the early years. On 6 July 1971, Van Ravesteijn wrote to Yutaka Matsuzawa, telling him that he should not bring too many works of art with him: ‘Our gallery is more an information centre than a real exhibition space and our accommodation to hang prints, documentation and paintings on the wall is rather poor!’24 In this respect, Art & Project could rightly call itself a conceptual art gallery: there was hardly anything to see in it, but there was a lot of documenting going on. In this context, ‘documentation’ is a multifaceted concept that can involve both primary and secondary documentation, or be purely informative or scientific by nature.25 A good example of the role of documentation at Art & Project is provided by its 1970 summer exhibition, which not only included works by Ger van Elk and Stanley Brouwn, but also documentation on more than 20 other artists, including Sol LeWitt, Jan Dibbets, Daniel Buren, Hanne Darboven, Keith Arnatt, Sigmar Polke, Ed Ruscha and the Japanese group Seishin Seigaku Kenkyūjo (Fig. 15). Both the exhibition and the documentation present were announced in mailshots.26

From the gallery’s correspondence, especially by Van Ravesteijn, with numerous artists, booksellers, publishers, libraries and collectors, we can learn how to understand Art & Project’s role as a ‘documentation centre with sales section’. Van Beijeren was a long-time librarian at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and aware of the latest publications. Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn maintained close contacts with artists, museum curators and gallerists of related international galleries. They travelled extensively both at home and abroad to visit artists and collectors and see exhibitions. This network of ‘like-minded people’ exchanged a lot of information and documentation.27

The Art & Project Bulletin, which received many positive reactions right from the start, played an important part in this exchange. The interest in the bulletin spread like wildfire, ignited by Lawrence Weiner, Jan Dibbets, Seth Siegelaub and others and with that, the attention to the gallery and its activities grew. Countless letters inquired about the bulletin, artists asked about the possibility of producing their own bulletin or other art publications, libraries asked to be sent publications.

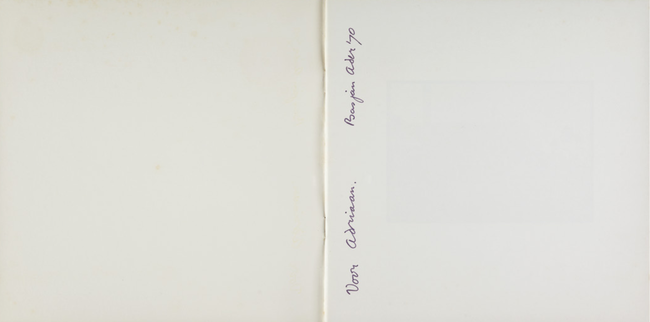

Particularly Weiner’s Bulletin 10, published in September 1969, generated a lot of response, especially from artists such as Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Sol LeWitt (Fig. 17). As mentioned, the collaboration with Weiner also lead to the production of Art & Project’s first artist’s book in 1971. Correspondence on the subject began as early as 1970. Weiner revealed that ‘to number the book I am afraid to its being taken for an unique object, much as a print or such! All the work in the book shall not be for sale . . .’ Weiner also doesn’t have high hopes for the proceeds: ‘. . . since most of the books have been given away I imagine that all profits will allow us to have a broodje kaas [cheese sandwich] if we look for a cheap snack bar.’28 Bas Jan Ader, working on his booklet Fall in 1970, also informed Van Ravesteijn that he liked the idea ‘. . . that a lot of people could have their own copy. So it has to be cheap. You are in business, so you should know how much you want per copy. For me, $1 a copy is okay. Just tell me what Europe distribution should be like.’29 (Fig. 18) Gilbert & George had similar intentions when, also in 1970, they informed Van Ravesteijn that they would send the gallery 100 copies of their recently-published booklet The Pencil on Paper Descriptive Works of Gilbert and George the sculptors.

We are anxious that copies should be widely and well distributed. We would like you to send 100 copies in Holland only. Konrad Fischer is sending in Germany and others and we are sending in England. We have sent you the booklets already enveloped each containing a ‘compliments of a&p’ slip.30

The number of mainly conceptual publications grew steadily in the early 1970s. Van Ravesteijn and numerous individuals and institutions mutually exchanged, bought and sold publications, including their own artists’ books. Art & Project ordered five copies of Mel Bochner’s 11 Excerpts at Galerie Sonnabend and ten copies (with bookshop discount) of Edward Ruscha’s Dutch Details at Stichting Octopus. The Centro Di in Florence (an institution that mainly documents visual art) proposed to swap publications, as sales were down. The correspondence in which these transactions are made suggests that sales (of artists’ books, catalogues and magazines) were anything but profitable and that the exchange of publications was the main purpose (Fig. 16).31

A deal made with art magazine Studio International was more commercial. In 1972, editor Barbara Reise sent a letter announcing her intention to produce an artist’s publication by John Baldessari. The proposal – the artist’s express wish – was to distribute Ingres and other Parables not only through the magazine, but also through the galleries that represented the artist in the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Italy and England. Van Ravesteijn concurred, on condition that Art & Project ‘was awarded’ the distribution of the publication in the Benelux countries, to which Reise agreed. The gallery used a simple mailshot to announce the publication in early 1973.32

Fig. 17 Bulletin 10: Lawrence Weiner, September 1969

Fig. 18 Bas Jan Ader, Fall, 1970, signed copy, Art & Project Archive, no. 1375

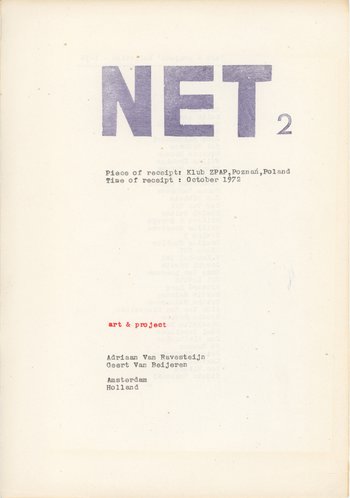

The fact that Art & Project’s network sometimes extended beyond the usual suspects is evidenced by, for one thing, its contacts with Poland, which was very isolated at the time – the country’s need for information and documentation in the form of books and magazines was substantial. ‘We are hungry about any information,’ Polish critic Andrzej Kostołowsky wrote to Van Ravesteijn on 21 October 1970. Correspondence between Van Ravesteijn, Kostołowsky and various Polish artists, including Jarosław Kozłowski, soon ensued. Publications were exchanged regularly as well. The gallery sent a dozen bulletins; from Poland came several conceptual publications and some proposals for bulletins, including one by Zbigniew Gostomski. At the end of October 1972, an exhibition of the first 56 issues of the Art & Project Bulletin took place at Klub ZPAP in Poznan, perpetuating the Polish connection.33 (Fig. 19)

Fig. 19 Announcement Art & Project Bulletins 1-56, exhibition October 1972, Klub Zpap, Poznan

Meanwhile, the (international) demand for both new and old issues of the bulletin increased annually and became a cause for concern. In August 1972, Van Ravesteijn reported to John Baldessari that sending bulletins by ‘airmail’ had become too expensive.34 This is why Van Ravesteijn regularly asked interested parties to contribute to the (shipping) costs. That these costs had already risen to a high level by 1970 is clear from a draft for a mailshot (which was never sent) inviting interested Dutch people to sign up as ‘members of Art & Project’. For a contribution of 10 guilders towards postage costs per calendar year, members would not only receive the gallery’s publications free of charge, but would also ‘allow us to continue to distribute our publications free of charge’ to ‘non-members outside the Netherlands’.35 The text of the mailshot once again underlines the importance – and extent – of the bulletin’s international distribution. When Van Ravesteijn was in Tokyo in the spring of 1970 and distributed some bulletins from there, a contribution towards the cost of sending those issues was also requested in an invitation.36

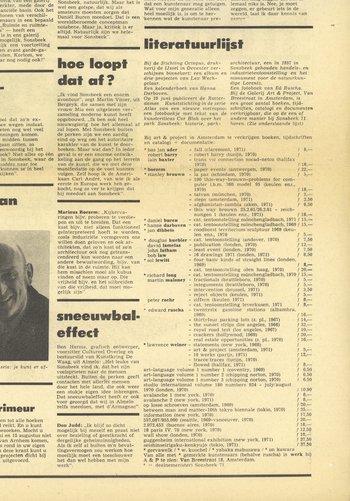

The gallery’s ‘sales section’ also proffered a large number of international art publications in the field of conceptual art, including its own publications. Mailshots kept its Dutch contacts informed of the appearance of its own publications as well as, on occasion, of the upcoming sales of other publications. On 1 May 1971, for example, the gallery published a list of artists’ publications by mainly conceptual artists. In addition to the aforementioned booklet by Bas Jan Ader (Fall, 1971), it included publications by Jan Dibbets (Roodborst Territorium), no less than seven publications by Lawrence Weiner, including Statements (1968), and the gallery’s own publication from that same year. Publications by Robert Barry, Marinus Boezem, Stanley Brouwn, Sol LeWitt, Martin Maloney, Peter Roehr and six artists’ books by Ed Ruscha as well as exhibition catalogues with regard to Hanne Darboven, Daniel Buren and Richard Long were also on the list. Issues of the magazines Art-Language, Studio International and Avalanche were available at the gallery. In addition, the list included the catalogues of the exhibitions Information in New York in 1970, 557,087 and 955,000 in Seattle in 1969 and Vancouver in 1970 respectively, and of the 1970 Tokyo Biennale.37 Most artists’ books were priced under 10 guilders; most catalogues around 15 guilders. Many of these are now in the canon of conceptual art publications and can only be found in antiquarian bookshops for high prices.

But the gallery not only kept its own network informed. An identical list of books appeared in the special newspaper that was published on the occasion of the 1971 Sonsbeek buiten de Perken exhibition (Fig. 20).38 This newspaper also stated that work by the majority of these artists was on show at Art & Project. Most of them, incidentally, were also represented at the Sonsbeek exhibition, since Van Beijeren was involved as one of the catalogue editors.

Fig. 20 Advertisement for artists' books at the Sonsbeek exhibition in 1971

One of the artists on the list whose work was not shown at Art & Project was Ed Ruscha. There was early contact with him through gallery owner Riekje Swart, and the gallery’s collection of artists’ books included many publications by Ruscha, one of the main pioneers of artists’ books. But these contacts never developed into a closer collaboration between artist and gallery. In 1969, Ruscha offered Art & Project an exhibition of his photo series Five 1955 Girlfriends. Van Ravesteijn was initially enthusiastic and suggested Ruscha create a bulletin around the series. The presentation in Amsterdam at the same time would be a great opportunity to sell his books. But because of an earlier presentation and publication of the series at the Conception exhibition in Leverkusen, Van Ravesteijn cancelled the project and asked Ruscha to propose a new one. After Van Ravesteijn left for Tokyo, the contact broke down. A few years later, in 1972, Van Ravesteijn made another unsuccessful attempt. Ruscha’s publications remained largely unsold fixtures in the gallery.39

Other books hardly sold, either; most of them remained on the shelves for years. The fact that most of the publications turned out to be of interest to only a small audience will also have played a part (Fig. 21).

‘Our Gallery Is More an Information Centre than a Real Exhibition Space’

Artists’ publications and documentation have been of great significance to Art & Project’s role as a conceptual art gallery. The Art & Project Bulletin, which rapidly evolved from an information sheet to an artist’s publication, was undoubtedly the gallery’s most important contribution to conceptual art. The bulletin was a unique find. The medium’s success and wide circulation largely defined Art & Project’s image and international reputation.

Previously overshadowed by the bulletin, the gallery’s more than 300 mailshots about all of its activities are increasingly recognized as important documentation and as a source of information.

Another underemphasized aspect is the part the gallery played in the documentation of art and in the production, distribution and sale of artists’ publications, not only its own, but also those of related institutions and artists. This, too, contributed to the creation of a lively international exchange in its own network.

That Art & Project was initially more of an ‘information centre’ than a ‘real exhibition space’, as Adriaan van Ravesteijn wrote to Yutaka Matsuzawa in 1971, may have been partly due to the limited space available in the early years, but the fact is that the gallery saw documentation and information as a natural part of its mission. Even after conceptual art had passed its zenith and the gallery had spread its wings and become more of a ‘real exhibition space’, documenting continued to be second nature to Art & Project.

Fig. 21 Joseph Kosuth, Function, Funzione, Funcion, Fonction, Funktion, Torino 1970

Notes

1 This article is also published in: Jannet de Goede and Lisette Pelsers (ed.), Art & Project: A History, Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum; The Hague: RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History; Rotterdam: nai010 publishers 2023. The Art & Project archives are now accommodated at the RKD, the Netherlands Institute for Art History; inv. no. 0748, hereafter cited as Art & Project archives. The artists’ books are also described separately in the RKD’s library catalogue and can be found here. The collection of secondary literature, initially housed at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, was transferred to the RKD in 2019.

2 For the various Art & Project publications, see here.

3 The complete quote reads: ‘Artists’ books are, like any other medium, a means of conveying art ideas from the artist to the viewer/ reader. Unlike most other media they are available to all at a low cost. They do not need a special place to be seen. They are not valuable except for the ideas they contain. They contain the material in a sequence which is determined by the artist. (The reader/ viewer can read the material in any order but the artist presents it as s/he thinks it should be). Art shows come and go but books stay around for years. They are works themselves, not reproductions of works. Books are the best medium for many artists working today. The material seen on the walls of galleries in many cases cannot be easily read/ seen on walls but can be more easily read at home under less intimidating conditions. It is the desire of artists that their ideas be understood by as many people as possible. Books make it easier to accomplish this.’ In: Art-Rite 14 (Winter 1976/1977), p. 10.

4 On artists’ books, see: Rob Perrée, Cover to cover: Het kunstenaarsboek in perspectief (Rotterdam, 2002); Anne van der Zwaag, Het kunstenaarsboek als wetenschappelijke bron: Een onderzoek naar de collectie kunstenaarsboeken uit de jaren zestig en zeventig van de twintigste eeuw in de Letterenbibliotheek te Utrecht, 2 vol., Utrecht, [2003]; Anne Moeglin-Delcroix, Esthétique du livre d’artiste: Une introduction à l’art contemporain, Paris 2011; Clive Phillpot, Booktrek: Selected Essays on Artists’ Books (1972–2010), Zurich, 2013; Andrew Roth, Philip E. Aarons and Claire Lehmann (eds.), Artists Who Make Books, London 2017.

5 Lucy Lippard, ‘Escape Attemps’, in: Six Years: The Dematerialisation of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 , New York 1973, pp. vii-xxii.

6 Robert Barry, All the things I know but of which I am not at the moment thinking - 1:36 PM; June 15, 1969 , Amsterdam [1974], the publication appeared on the occasion of an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. In that same year, Art & Project published an artist’s booklet by Barry. Bulletin 17 (1969) shows Barry’s During the exhibition the gallery will be closed; the title of Barry’s artist’s book, published by Seth Siegelaub in 1969, is Inert Gas Series/Helium, Neon, Argon, Krypton, Xenon/From a Measured Volume to Indefinite Expansion.

7 See, for example: Suzanna Héman, Jurrie Poot and Hripsimé Visser (eds.), Conceptuele kunst in Nederland en België 1965–1975: Kunstenaars, verzamelaars, galeries, documenten, tentoonstellingen, gebeurtenissen, exh. cat. Amsterdam/Rotterdam: Stedelijk Museum 2002; Peter Osborne (ed.), Conceptual Art, London 2002; Alexander Alberro, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity, Cambridge, MA 2003; Nathalie Zonnenberg, Conceptual Art in a Curatorial Perspective: Between Dematerialisation and Documentation, Amsterdam 2019.

8 Ton Geerts, ‘Art & Project (1968-2001)’, RKD Bulletin 1 (2012), pp. 24-30.

9 Camiel van Winkel, ‘Het dwangbeeld van een puur idee’, in: Héman, Poot and Visser, Conceptuele kunst in Nederland en België, op. cit (note 7), 38; also see: Camiel van Winkel, During the exhibition the gallery will be closed, Amsterdam 2012.

10 Leontine Coelewij and Sara Martinetti (eds.), Seth Siegelaub: Beyond Conceptual Art, exh. cat. Amsterdam/Cologne: Stedelijk Museum 2016; Michalis Pichler, Books and Ideas After Seth Siegelaub, New York, 2016; Marja Bloem et al. (eds.), Seth Siegelaub: ‘Better Read Than Dead’: Writings and Interviews, 1964-2013, London/Amsterdam, [2020]; Kasper Andreasen, ‘“Activist ja, maar niet als kunstenaar.” Gesprek met Seth Siegelaub’, De Witte Raaf 211 (May-June 2021).

11 Jan Dibbets, Roodborst territorium/sculptuur 1969, april-juni; Jan Dibbets: Robin Redbreast’s territory/sculpture 1969, april-june; Jan Dibbets: domaine d’un rouge-gorge/sculpture 1969, avril-juin; Jan Dibbets: Rotkehlchenterritorium/Skulptur 1969, April-Juni , New York/Cologne: Seth Siegelaub, Walther König 1970.

12 See, for example: Coelewij and Martinetti, Seth Siegelaub, op. cit. (note 10), 116-126. The title of this publication officially reads Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner. A second edition was published by Roma Publications, Amsterdam, in 2015.

13 On the Art & Project Bulletin, see: Regine Ehleiter, 'The Art & Project Bulletins As a Site of Exhibition, Experimentation and ‘International’ Exchange', in: Jannet de Goede and Lisette Pelsers (ed.), Art & Project: A History, Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum; The Hague: RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History; Rotterdam: nai010 publishers 2023, pp. 180-193.

14 Ton Geerts, ‘Interview with Adriaan van Ravesteijn on the Art & Project Bulletins, May 17, 2011’, in: Louisa Riley-Smith (ed.), Art & Project Bulletins 1-156, September 1968-1989, London/Cambridge/Paris, 2011, p. 82.

15 The Information (1970) exhibition at MoMA in New York featured 23 issues of the bulletin. The Muramatsu Gallery in Tokyo probably also displayed a number of bulletins between 29 July and 4 August 1970. In late October 1972, Klub ZPAP in Poznan, Poland, showed the first 56 issues of the bulletin. On this subject, see: Ton Geerts, ‘Art & Project Bulletins: De Poolse connectie/Art & Project Bulletins: The Polish Connection’, RKD Bulletin 1 (2017), pp. 37-41.

16 Kunst als boek, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 15 December 1972–7 January 1973; the exhibition was accompanied by a stencilled list of the books on display, including 13 issues of the Art & Project Bulletin. Incidentally, all the books and magazines on display seem to have come from the gallery.

17 Most of the booklets were printed at Drukkerij Delta in The Hague, which also printed the bulletins; archives A&P, inv. no. 246.

18 Johan Pas, Multiple/Readings: 51 kunstenaarsboeken 1959–2009, 2 vol., Ghent, 2010, section Readings, 28.

19 Richard Long, From along a Riverbank, leaves on paper, 9 parts, each 20.7 × 19.5 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv. no. KM 130.731.

20 Philpott, Booktrek, op. cit. (note 4), p. 107.

21 Art & Project often loaned works and books to the Neudeflat exhibitions, for example for the 1971 exhibition Taal-kunst. Een faset van konseptuele kunst, curated by students Evert van Straaten and Jeroen Grosfeld. On 8 February 1972, Van Ravesteijn reported to Stanley Brouwn that all of the exhibited objects had been returned to the gallery and that no fewer than two booklets had been sold. Archives A&P, inv. no. 488. One of the organizers of the exhibitions, Frans Haks, was responsible for the acquisition of artists’ books for the Kunsthistorisch Instituut in Utrecht. He regularly purchased artists’ books at Art & Project. See: Van der Zwaag Het kunstenaarsboek als wetenschappelijke bron, op. cit. (note 4); and Nadine Orth, ‘De stem op de negende etage: Een onderzoek naar de tentoonstellingen in “N9”, seizoen 1971–1972 bij de Utrechtse Kring, georganiseerd door een werkgroep van het Kunsthistorisch Instituut onder leiding van Frans Haks en Carel Blotkamp’ (Master’s degree thesis in Art History, Utrecht University 2008), p. 26 (Note 63).

22 Philpott, Booktrek, op. cit. (note 4), p. 192.

23 Ibid., p. 193.

24 Message from Adriaan van Ravesteijn to the author, 26 August 2008; also see: Alied Ottevanger, ‘Dear Adriaan and Geert/Beste Adriaan and Geert: Elf kunstenaarsbrieven uit het archief van Art & Project’, Jong Holland 13/2 (1997), p. 77 (Note 51).

25 On the importance of ephemeral printed matter, see: Pilar Perez (ed.), Extra Art: A Survey of Artists’ Ephemera, 1960-1999, Santa Monica 2001; David Senior (ed.), Please Come to the Show (London, 2014); Barbara Preisig, Mobil, autonomy, vernetzt: Kritik und ökonomische Innovation in Ephemera der Konzeptkunst, 1966-1975, Munich 2018; Bruno Tonini, Artists’ Invitations 1965–1985, Fusignano 2019; Johan Pas, ‘Van aperitief tot dessert of hoe de uitnodiging kunstwerk werd’, Rode Haring 4 (July 2021), pp. 24-43.

26 Letter from Van Ravesteijn to De Nederlandsche Bank, 14 May 1971; archives A& P, inv. no. 201.

27 Letter from Van Ravesteijn to Yutaka Matsuzawa, 6 July 1971; archives A&P, inv.no. 575.

28 Mailshot by Art & Project for the exhibition Summer 14.7-15.8 1970.

29 See, for example: Christian Berger and Jessica Santone, ‘Documentation as Art Practice in the 1960s’, Visual Resources 32/3-4 (2016), pp. 201-209; Catherine Moseley (ed.), Conception: Conceptual Documents 1968 to 1972, Norwich, 2001.

30 See: Sophie Richards, Unconcealed: The International Network of Conceptual Artists 1967-77: Dealers, Exhibitions and Public Collections, London, 2009.

31 Letter from Lawrence Weiner to Van Ravesteijn, 26 October 1971; archives A&P, inv. no. 637.

32 Letter from Bas Jan Ader to Van Ravesteijn, 23 November 1970; archives A&P, inv. no. 460.

33 Letter from Gilbert & George to Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn, 22 May 1970; archives A&P, inv. no. 533.

34 Correspondence with Centro Di, 16 December 1971; archives A&P, inv. no. 201.

35 Also see the letter from Barbara Reise to Van Ravesteijn of 13 May 1973 in which she explains the distribution options less formally; archives A&P, inv. no. 838 (artist’s file John Baldessari).

36 Geerts, ‘Art & Project Bulletins’, op. cit. (note 15), pp. 37-41.

37 Letter from Van Ravesteijn to John Baldessari, 12 August 1972; archives A&P, inv. no. 344.

38 Unsent mailshot, archives A&P, inv. no. 209.

39 This mailshot reads: ‘Van 4 februari tot 15 april 1970 zal art & project in tokio gevestigd zijn . . . er zullen daar enkele bulletins worden samengesteld die op de bekende manier worden verspreid/ in verband met de hoge kosten . . . zou een bijdrage zeer welkom zijn . . . 11.1 1970; Art & Project, Richard Wagnerstraat 8, Amsterdam.’ It was addressed to a specific group of people: Hieron Pessers, Anni Apol, Dolf Stam, Aafke van der Made, Roelf van Bergen, Marijke van der Wijst, Leopold van Ravesteijn, Leo and Vera Schrader, Frans Haks, Joke Heideman, Ton Raateland, Paul and Coosje Kapteyn, Liesbeth Brandt Corstius, Richard Padovan, Riekje Swart, Ronald Snijders, Crissy van Bennekom, Walter Kous, Louise van Bree, Gosse and Jacqueline Oosterhof, Friso Broekema, Reinier Schoorl, Rini Dippel, Maarten and Alphien van Regteren Altena, Johan Ambaum, Toon ter Mors, Frits and Agnes Becht, Frans Vervenne, Wies Smals, Onno Boers, Frans Molenaar, Jochem and Erna van Loghem, Geert-Jan Visser, Luca Dosi Delfini, Arthur Rijsbosch, Rein-Arend and Ank Leeuw, Hans van Manen, Albert Waalkens, Mia van het Hart, Enno Develing, Jan and Nettie Sommers, Egbert Switters, Paul and Wiesje Schwarz, Jaap Bremer, Will Ledel, Herman and Henriëtte van Eelen, Wil de Vries, Marten Kircz, Justus and Greet Halbertsma, Hypolite de Ruyter, Wijnand and Annet Wildenberg, Jaap and Jetteke Bolten, Martin and Mia Visser, Benno Premsela, Carel and Hoos Blotkamp.

40 On 1 May 1971, the gallery sent out a mailshot containing a list of available publications; archives A&P, file Mailshots.

41 ‘Literatuurlijst’, in: Aktiviteit Sonsbeek 71 [1971], p. [9].

42 For the correspondence between Riekje Swart, Adriaan van Ravesteijn and Edward Ruscha, see archives A&P, inv. no. 418.