Art & Project: A Short History

Ton Geerts

In September 1968, Adriaan van Ravesteijn (1938-2015) and Geert van Beijeren (1933-2005) opened a gallery in Van Ravesteijn's parental home in Amsterdam's Richard Wagnerstraat.1 The space was no more than a side room measuring 4 x 3 metres with an adjoining passage and a documentation table on the landing. Van Ravesteijn had studied architecture for several years at Delft University; Van Beijeren was working as a librarian and later became a curator at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Both were familiar with the Amsterdam art scene, which at that time comprised just a handful of modern art galleries. They regularly helped out at Riekje Swart's gallery - one of the few operating internationally - where they became acquainted with the gallery's artists, including Ad Dekkers, Peter Struycken, Ger van Elk, Jan Dibbets and Marinus Boezem.2

The combination of Van Ravesteijn's interest in the cross-fertilisation between architecture and fine art and Van Beijeren's knowledge of and contacts in the art world of the late 1960s gave rise to a new phenomenon in the small Amsterdam gallery scene.

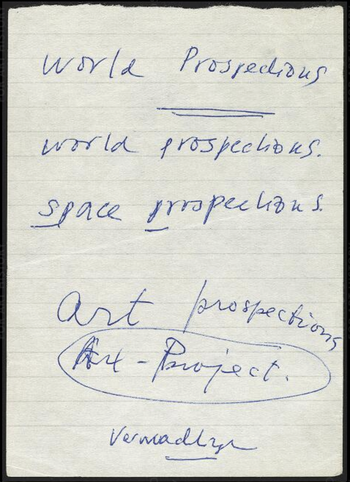

First 'draft' about the name Art & Project; Archief Art & Project, nr. 202

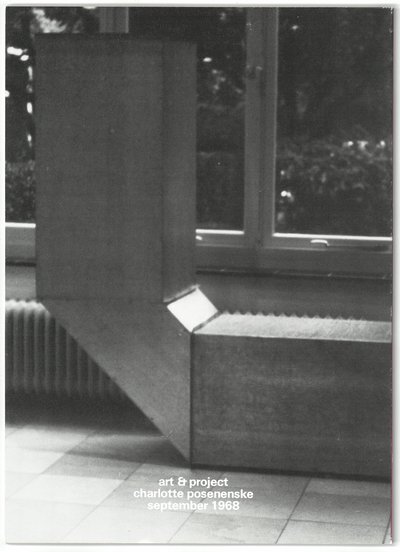

Art & Project, as their enterprise was named - the term gallery being deliberately avoided - initially focused on exhibitions or projects that paid particular attention to space. Art & Project, stated the first in the series of folders produced to accompany the exhibitions, plans to bring you together with the ideas of artists, architects and technicians to discover an intelligent form for your living and working space. 'Art & Project invites you to participate in its exhibitions which will explore ways in which art, architecture and technology can combine with your own ideas.' Hence, the artists invited to make the first exhibitions were chosen for their ability to conform to the (modest) available space, thereby giving it a new form. Among the exhibitors was the German Minimalist artist, Charlotte Posenenske. Her stereometric galvanised and cardboard elements could be combined in different ways and were intended as interventions in the space. This was also true of the cuboid constructions by the architects Slothouber and Graatsma, the inflatable sculptures by Danish sculptor Willy Ørskov, and lamps by the architect Aldo van den Nieuwelaar.

Charlotte Posenenske at Art & Project, september 1968

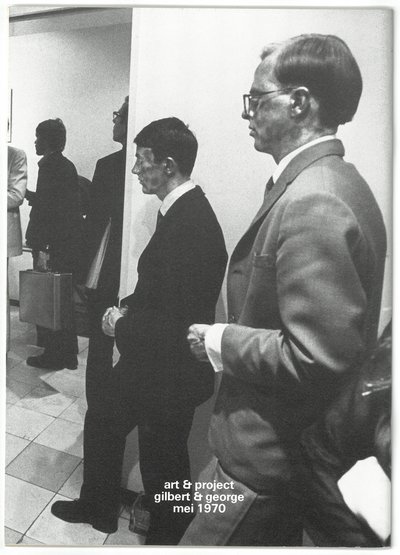

The collaboration with architects initially envisaged in Art & Project's manifesto never really took off. En route the course shifted towards Conceptual Art, which by the end of the 1960s was an ever-stronger presence in the international scene. Art & Project became an exponent of an emerging generation of artists and art dealers who wanted to bring artists and audiences together in new ways. Galleries no longer needed to be well-equipped spaces, especially designed for the exhibition of paintings or sculptures, but could now also be housed in alternative, confined spaces which, in all respects, looked like anything but a gallery. The new galleries were idealistic and averse to the traditional professionalism practiced in the 1960s in what had become known as 'poen' or dosh, galleries. Moreover, there was a group of artists who no longer felt the need to make material art and devised concepts that were not directly bound to time, space or a specific location. One of them was Stanley Brouwn, who Van Beijeren met in the Stedelijk Museum library. A stream of new artists and ideas came into the gallery through Brouwn. During this celebrated period, Art & Project showed work by artists such as Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, Jan Dibbets, Ger van Elk, Robert Barry, Stanley Brouwn, Douglas Huebler, Gilbert & George, Daniel Buren and Hanne Darboven.

Gilbert & George performance at Art & Project, 1970

This conceptual programme introduced Art & Project into an international circuit of likeminded artists and dealers, and the gallery built up a considerable reputation beyond the Dutch border. Operating somewhat at a remove from the traditional galleries in the centre of Amsterdam, Art & Project from the start created a profile for itself as the most internationally oriented and innovative gallery in the Netherlands.

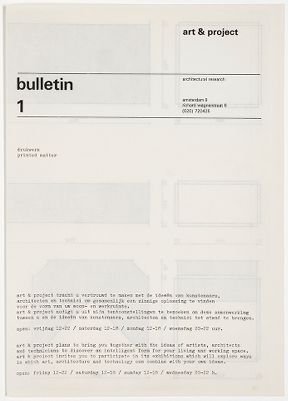

BULLETINS

Art & Project's reputation was also founded on the Bulletins it produced, which were distributed to interested parties from the very first exhibition.3 Because of the gallery's eccentric location, Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn felt they should provide more information than was usual on the traditional invitation card. A Bulletin consisted of a single A3 sheet folded double to make a four-page folder. It was printed in an edition of 800, 400 to 500 of which were mailed out, while the remainder was available in the gallery. The layout, using very simple and clear typography, remained unchanged from the first issue in 1968 to the last one in 1989. The Bulletin not only accompanied the exhibition, it sometimes, for instance in the case of Lawrence Weiner, formed part of the exhibition. At the height of conceptual Art, between 1967 and 1973, the Bulletin became an essential medium for the gallery. Artists were given free rein to fill the Bulletin in any way they pleased, within the limits of the existing simple, folded-A3 layout.

Charlotte Posenenske en uitgegeven door Art & Project

Art & Project Bulletin #1, 1968

Den Haag, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Archivalia)

The international mailing list for the Bulletins began to grow through Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk's extensive networks and Geert van Beijeren's contacts at the Stedelijk Museum. Conceptual Art, after all, was art without borders and thus essentially international.4 Exhibitions, projects and artists were able to move around easily, even to show simultaneously at different locations. Robert Barry, for example, orchestrated seven simultaneous exhibitions in different locations. He sent out an Art & Project Bulletin bearing the text: 'During the exhibition the gallery will be closed' and the same exhibition was held at Gallerie Sperore in Turin and at Eugenia Butler in Los Angeles. In the international network Art & Project now belonged to, one gallery could announce the next exhibition at another gallery, or the exhibition was not held at a fixed location at all, but a Bulletin was sent instead from Düsseldorf, Venice or Tokyo. The magic of the Bulletin stemmed not only from the vast range and quality of the artists? contributions, but also simply from the consistent numbering of the Bulletins (1-156), which considerably enhanced the appeal of collecting them; some Bulletins even soon became collectors' items.5

NEW PATHS

Art & Project was not a gallery for consolidation. Moving premises was vital for renewal. The gallery left Richard Wagnerstraat in 1971 and moved temporarily to a building a stone's throw from the Stedelijk Museum, at 18 Van Breestraat. Richard Long and Sol LeWitt joined the gallery here. In 1973 it moved to a more spacious home on the Willemsparkweg and, in 1979 it moved one more time in Amsterdam, this time to the Prinsengracht. Each move was accompanied by a shift in programming. The newer, larger and lighter spaces offered more possibilities for showing painting and sculpture. After the heyday of Conceptual and Minimalist Art, on the Willlemsparkweg and the Prinsengracht, the gallery focused on a new generation of artists who rejected the concept-based art of the 1960s and 70s. Surprisingly enough, it was Art & Project who first introduced artists from the so-called Italian transavantgarde - Enzo Cucchi, Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente and Mimmo Paladino - to the Netherlands. New relations also took root with a group of British sculptors including Alan Charlton, Nicholas Pope and Barry Flanagan. In the same period, Art & Project was operating within a broad network of galleries and collectors throughout Europe. Over the years they began to show more and more Dutch painters and sculptors, including Carel Visser, Daan van Golden, Ben Akkerman, Han Schuil, Joris Geurts, Ab van Hanegem and Leo Vroegindeweij.

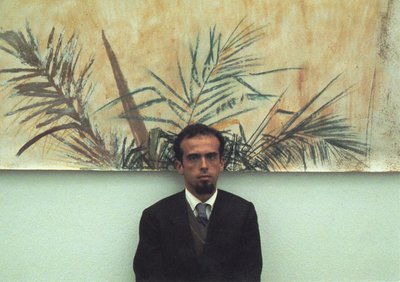

Francesco Clemente, invitation card

In 1990 the rigorous and definitive decision was taken to bid farewell to the Amsterdam art world and move the gallery to the North Holland village of Slootdorp. The gallery occupied the former community centre of the Jewish work village Nieuwesluis, which in the 1930s had housed Jewish refugees from Germany while they prepared, through work, for a new life in Palestine. Art & Project continued to hold exhibitions, but now without the Bulletins and without all the fuss and bother of the ever expanding commercial art market which, in the view of Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn, clouded a love of art. In 2001, after 320 exhibitions by 95 different artists, one of the internationally most renowned galleries of the Netherlands closed its doors. Now it was time to take stock.

Art & Project in Slootdorp

ART & PROJECT ARCHIVE

Geert van Beijeren and Adriaan van Ravesteijn always documented their activities in minute detail, which gave rise to an exceptional archive. The Art & Project archive was transferred in sections to the RKD when the gallery closed in 2001 and covers the entire period that the gallery was active, from 1968 to 2001. Besides general correspondence with museums, galleries and other art institutions at home and abroad, it contains neatly ordered files on each artist with archival and photographic material, both on individual works and gallery installations. The archive also encompasses records and documentation relating to the running of the gallery (acquisitions, contracts, correspondence with artists), photographic and press documentation, and small-scale printed matter like invitation cards and posters. All items and correspondence relating to the preparation of the Art & Project Bulletins, with contributions by artists, are also stored in the archive. A separate section comprises boxes, ordered by artist, with (some rare) artists’ books and monographs and assorted realia (including mail art and artists’ attributes). This library is contained in its entirety in the Art & Project archive.

Altogether, uninventoried, this archive and library are around 92 metres long.

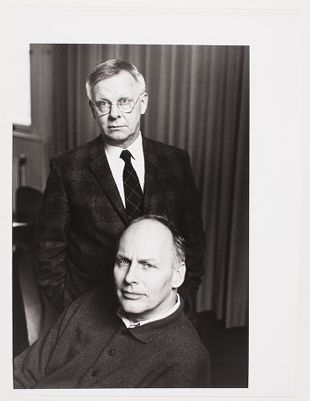

Helena van der Kraan

Portret van Geert van Beijeren en Adriaan van Ravesteijn

Rotterdam, Axel en Helena van der Kraan

THE ART & PROJECT / DEPOT VBVR COLLECTION

Besides the extensive archive, Geert van Beijeren and Adriaan van Ravesteijn (VBVR) also accumulated a considerable art collection, which Van Ravesteijn described as follows in 1999:

A gallery collects artists and garners an early mention in their biographies. It prefers to leave art collecting to the “real” collectors. But the accumulation that nevertheless takes place over the years has to occur somewhat surreptitiously, otherwise you find yourself competing with your customers. In the mid-1970s, when we were on the Willemparksweg, we came up with an advertisement for Art & Project which was a photo of the interior of the gallery during an exhibition in which Geert van Beijeren and I – coats and hats on – pose as visitors. The accompanying text reads: “We think what we do is so interesting, we regularly visit our own gallery”. ‘This advertisement was never used. We realised that this kind of bravado would only work against us: you have to be careful not to give the impression you’re keeping the best bits for yourselves. Most of the works we ultimately kept had been sitting unsold for years. As they moved with us, like loyal companions, from one house to the next, they gradually revealed to us how indispensable they were. If, later, someone showed an interest in one of these works after all, we were seized by a furious passion, like a mother whose children are in danger. We hid it under the bed, pretended we had given it as a birthday present or, if that didn’t help, the aspiring buyer was rendered harmless through hypnosis.

In that respect our purchases from fellow galleries were considerably simpler. Then we were the customer and just paid the bill. This is how we added art works to the collection, which then placed the work of our ‘own’ artists in a broader context, or provided contrasts, introducing an extra dimension. does this mean there is a collection after all?6

Looking back, this ‘collection’ of more than 850 works cannot be seen as a private collection built up according to specific criteria. Its creation cannot be divorced from Art & Project. A gallery’s ‘trade stock’ grows in fits and starts, and in passing. It is in no sense a thoroughly considered process of collecting. Only when Art & Project closed at the end of 2001 was it possible to take stock. The ‘stock’ that was transferred to Art & Project / Depot VBVR is a reflection of the gallery’s programme and in many cases the development of the individual artists who were connected to it.

The works were housed in a number of museums, which Van Beijeren and Van Ravesteijn selected very carefully, taking the existing collections into account. The heart of the collection (approximately 450 works) was on long-term loan to the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede. The emphasis here lied on large clusters and/or seminal works by artists such as Alan Charlton, Francesco Clemente, Adam Colton, Tony Cragg, Ad Dekkers, Ger van Elk, Barry Flanagan, Joris Geurts, Jos Kruit, Richard Long, Juan Muñoz, nicholas Pope, Han Schuil, Peter Struycken, David Tremlett, Richard Venlet, Toon Verhoef, Emo Verkerk, Carel Visser and Leo Vroegindeweij, with sculpture being the most strongly represented discipline.

A one day walk / Anthony Caro, Philip King, Hamish Fulton, Nicholas Pope, Barry Flanagan, Tony Cragg, Bill Woodrow Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In 2013, Adriaan van Ravesteijn donated to the Kröller-Müller Museum the sculpture collection that until then had been housed at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, consisting of over 300 works. The remaining works, mostly paintings, were donated to the Rijksmuseum Twenthe.

Around 135 works by such artists as Ben Akkerman, Daan van Golden, Gerald van der Kaap, Rob van Koningsbruggen and Emo Verkerk were loaned to the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam houses a group of around 70 works by Robert Combas, Fons Haagmans and Salvo. More than 215 conceptual works from the period 1968-1975 by Robert Barry, Stanley Brouwn, Jan Dibbets, Daniel Buren, Gilbert & George, William Leavitt, Yutaka Matsuzawa, Allen Ruppersberg, Lawrence Weiner and others were initially taken as a subcollection by the Cabinet des Estampes du Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva, but moved - with curator Christophe Cherix - to New York in 2007 when it was gifted to the MoMA. Eventually, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam received four more paintings by Andrew Heard, a painting by Ger van Elk and one by Han Schuil and a series of cubic constructions by Slothouber/Graatsma.

The RKD worked with these museums to disclose this important collection, which has culminated in this joint publication in 2023. This not only contains all the art works in the Art & Project/Depot VBVR collection, but also an inventory of the Art & Project archive.7

Notes

1 A first version of this essay was first published in the RKD Bulletin 2012/1, pp. 24-30

2 For the history of Art & Project, see L. Dosi Delfini and M. van Nieuwenhuyzen, ‘Art & Project. Een terugblik op de vroege jaren’, Stedelijk Museum Bulletin (May/June 1995), pp. 58-59; T. Gubbels, Passie of professie: galeries en kunsthandel in Nederland, Abcoude 1999, pp. 90-94; R. Dippel, ‘Art & Project: The Early Years’, in: Chr. Cherix, In & out of Amsterdam: Travels in Conceptual Art, 1960-1976, New York 2009, pp. 23-33

3 The Bulletins are examined extensively in: Cherix 2009, and L. Riley-Smith (ed.), Art & Project Bulletins 1-156. September 1968-november 1989, London/Cambridge/Paris 2011. For a general orientation of the Bulletins: G. Allen, Artists’ magazines: an alternative space for art, Cambridge Mass./London 2011, pp. 235-236

4 The international network is examined in: S. Richard, Unconcealed: the international network of conceptual artists 1967-77: dealers, exhibitions and public collections, London 2009 and Cherix 2009, passim

5 T. Geerts, ‘Interview with Adriaan van Ravesteijn on the Art & Project Bulletins, May 17, 2011’, in: Riley-Smith 2011, pp. 63-84

6 Printed in a folder accompanying the exhibition 'Uit depot: Ruimtelijk werk in het bezit van Art & Project', 10 April-6 June 1999, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede

7 An online version in Dutch can be found here; for an English version in this RKD Study click here.